Announcements

Get free breathing and awareness practices, insights, and tips on my Facebook Public Figure Page

Organic Relaxation

To experience a sense of this relaxation, lie down comfortably on a mat or soft carpet with your hands on your belly. Check in on your breathing. As you do so, notice how you are completely supported by the earth. Really let yourself feel this support. Notice the thoughts and emotions that appear, along with the sensations of relaxation that are settling in. Just let them be as they are, without commenting on them or dwelling on them in any way.

Now pay particular attention to your back and spine. Take a few breaths to sense the interface, the vibratory sensation, between your back and the floor. Let your entire back release into the floor. Let your belly rise and fall with each inhalation and exhalation. Notice how your entire body, freed a bit from your identification with your thoughts, emotions, and efforts, begins to relax into emptiness and spaciousness. As this happens, you will sense your breath slowing down and becoming quieter, allowing a new, fuller sense of receptivity and presence to radiate from every aspect of your being. Notice also how more parts of your body are now involved effortlessly in your breath—and how you can now feel the multileveled movements of your breath inside the conscious spaciousness that you begin to sense is what you really are.

Copyright 2009, by Dennis Lewis. This passage is taken from my book Breathe Into Being: Awakening to Who You Really Are.

What Others Say About Breathe Into Being

“We all know that breathing is essential to life. But this book helps us to discover its immense importance not only to physical life, but to the very meaning of what we are and what we can become.”–-Jacob Needleman, author of Why Can’t We Be Good?, The American Soul, and What is God?

“Dennis Lewis has written a very wise and highly readable book about one of the most fundamental insights of the great spiritual traditions: the breath is a mediator between mind and body, and is a bridge to the transcendent. This is a marvelous guidebook in cultivating awareness and living in the now. All valid spiritual instruction is simple and unadorned — as simple as breathing, as Lewis makes clear in Breathe Into Being.”–-Larry Dossey, M.D., author of Healing Words and The Power Of Premonitions

“Breathe Into Being is both a fun and a must read, a fountain of practical wisdom for self-exploration that is delicious on the tongue of the soul while quenching our thirst for the knowledge of enlightenment. It is perhaps the most important self-help book – in the deeper sense of that expression – to come out in the new millennium.“–-Glenn H. Mullin, author of The Fourteen Dalai Lamas: A Sacred Legacy of Reincarnation

“Breathe Into Being is a most practical, user-friendly yet profound guide to awakening, with simple exercises that blow away the conditioned mind’s veils, allowing one’s inner light to shine forth. I highly recommend it.”–-Leonard Laskow, M.D., author of Healing with Love.

“Dennis is a master teacher who stands fast in the profound truth that when we welcome this moment just as it is, life works. How simple. How overlooked. How astonishing and wonderful. The secret he reveals: all that we need do is attend to our body’s natural function of breathing in, and breathing out. Nothing more is needed. Listen to Dennis. Breathe. Be still and awaken into living your alive, joyful and harmonious Presence that Dennis so beautifully reveals.”–-Richard Miller, PhD, author of Yoga Nidra: The Meditative Heart of Yoga (Sounds True), is president of the Center of Timeless Being and co-founder of the International Association of Yoga Therapists.

“A refreshingly simple, straightforward, and enjoyable exploration of the connections between body, breath, awareness, and presence. This user-friendly guidebook will help you be more embodied and awake.”–-John Welwood, author of Toward a Psychology of Awakening

“In light of our fast often distressful pace of living, when one can read something that is both interesting and inspiring yet slows us down to breathe easier and effortlessly in the moment, it is a very good thing. Dennis Lewis’ latest book Breathe Into Being does just that. Read it and let it breathe you.”–-Mike White, Director, The Optimal Breathing School and Institute

The Silence at the Heart of Being

All the great mystical traditions speak of a miraculous silence, or emptiness, that lies at the heart of being, at the heart of the kaleidoscope of life. These traditions refer to this silence not as an absence but rather as a fullness that is beyond description, beyond the reach of human thought, a fullness that, miraculously, is the very substance of our universe.

Modern science, too, seems to evoke this idea when it speaks of an almost infinite number of spinning galaxies in silent, expanding space or the dazzling dance of particles and waves that emerge out of the space/time continuum-where matter dissolves into energy, and energy into shifting configurations of something unknown.

Though it is impossible to describe this resounding silence, this over-flowing emptiness, the great traditions tell us that it is possible to experience it, here and now, as our own fundamental being, as our “Self,” as “I Am.” They also tell us that this experience, which is more aptly defined as a “non-experience,” is somehow both the beginning and the end of our possible spiritual evolution. They tell us that by returning to this primordial “source,” this psycho-spiritual “absolute,” we can be transformed and realize our highest potentials in the very midst of our everyday lives and of the life force that propels it.

To be sure, this return, though it requires an on-going, earnest search, takes place instantaneously. Every moment that we are awake and aware gives us a new opportunity to “listen” for this inner silence that somehow defines what we are in our very essence. To begin to live consciously thus means to turn toward our own inwardness, where the world of silence, of being, can come alive and can give substance and meaning to our words, actions, and perceptions.

The attempt to turn toward this silence is both a psychological and a metaphysical act. Psychological because it demands that we begin to free ourselves from our constant identification with the thoughts, feelings, sensations, goals, perceptions, and so on that somehow define our sense of ourselves; and metaphysical because it takes us into unchartered, perhaps even transcendent, territory, where we can experience an entirely new perspective, an expanded, more global sense of ourselves.

The effort to hear and attune ourselves to this inner silence can work magic in our lives: for this silence can not only heal us and give our lives meaning, but, perhaps even more importantly, it can bring us to the direct perception of who we really are. The tension, the polarity, created by our search for this silence and our need for outward manifestation can open up a new vision of ourselves, and with it an entirely new arena for self-study: our own apparent duality.

On the one side is the “call” of our inner being, fed by the depths of silence that somehow represent our innermost possibilities; on the other side is our constant urge toward manifestation, in which our thoughts, feelings, and sensations work to propel us outward toward the world around us. It is this seeming separation between the inner and the outer that gives us a new understanding of what it means to be whole, autonomous beings. For the inward call toward being and the outward urge toward manifestation complement and complete each other. The movement inward unchecked by the demand for outward manifestation turns into imagination and dreaming. And outward manifestation without an inner search is empty and simply creates confusion in both ourselves and the world. It is the silence encompassing both of these directions that can bring these two movements into harmony and put us into touch with a new, global awareness that embraces everything in our lives. From the perspective of this awareness, there is no duality; there is only the direct, non-dual perception of wholeness.

What can help bring us to this silence? It all begins with self-inquiry, self-interrogation. It is only when we are deeply in question that we become momentarily free from our conditioning and self-image and are open to the presence of silence–and truth–in ourselves. Self-inquiry may begin with a mental question such as “Who am I?”, but to have any real action on us the question mark must also reach into our heart and body. When it does, when we really need to understand, our questioning evokes a profound sense of spaciousness, an opening into silence itself.

There are many opportunities in the course of our daily lives to return to this silence, for the silence is always there at the heart of things. Through direct observation it is possible to see that everything that takes place in our lives is simply a superimposition over this silence. It is important, however, that we realize this silence is not itself an object, a thing, but is rather the very foundation of our being, the ultimate perceiver of all things. When listening occurs, it is silence that listens.

There are certain times and conditions when it is more possible to be attuned to this silence. Early in the morning just after waking up or at night just before falling asleep are both times when the silence can be experienced. Our conditioning has either not yet been put into motion or is in the process of relinquishing control of our organism, and our attention, if we allow it, can actually unfold into the silence.

Another situation in which it is possible to experience this silence is between two thoughts or activities, when the mind or the body is less active. To become open to the silence, however, requires that we consciously allow this gap to remain, not trying to fill it with some meaning or action as we habitually do. We can also return to this silence between two breaths, especially between the out-breath and the in-breath. When we practice this often we suddenly discover that the silence has always been there, just waiting for our return.

Finally, it is important to remember that this silence is not simply a psychological or physiological phenomenon, but is rather the essence, the background, of our being. The great spiritual traditions have spoken of this silence in their own way as God, Brahma, the Ultimate Perceiver, Nirvana, Wu Chi, the Absolute, and so on. What is important is not how it is spoken of, of course, but rather the recognition that the world of silence, which lies at the heart of our life force, gives birth to everything that we know and are. To lose touch with this world is to divorce ourselves from our own essential being–and to divorce the world itself from its own source. For it is silence that creates, and it is silence that perceives its creation.

Copyright 2007-2010 by Dennis Lewis

Self-Sensing and the Breath

Opening to the sensations of the body, which I often refer to as self-sensing, brings us into a more genuine relationship with ourselves, since it reveals how we actually respond to the inner and outer circumstances facing us. It also has a beneficial impact on our nervous system, helping to bring about the natural changes necessary for harmonious functioning and development. The human brain includes some 100 billion neurons, each of which “touches” some 10,000 other neurons. These neurons have many functions, but one of the main ones is to connect the various parts of the organism with one other, so that the organism as a whole can function in an integrated way while carrying out its activities. Through self-sensing we provide the organism with information it might not otherwise receive. We begin to learn firsthand about the interrelationships of our breathing, thoughts, emotions, postures, and movements. By noticing the sensations of our body, especially our breathing, in both the quiet and not-so-quiet circumstances of our lives, we experience connections between dimensions of ourselves that ordinarily escape our awareness. Self-sensing gives our brain and nervous system the spacious perspective it needs to help free us from our habitual psychophysical patterns of action and reaction. It helps free us from our various identifications and attachments with some function or manifestation of ourselves. When we pay choiceless attention to what is, we become one with awareness, with presence.

Try it now for a minute or two. Whatever position you are in, sense your entire body, including your breathing. Become innocently intimate with all the sensations that are occurring, opening as much as possible to them. Also include the shapes and energies of the thoughts and feelings that are taking place—negative or positive, it doesn’t matter. Don’t attempt to change anything. Simply get as close as possible to everything that is happening. Notice how allowing yourself to get closer to what is actually happening in your own body and mind seems to open up a much more spacious sensation of yourself, a sensation of “wholeness.”

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis. Passage from Breathe Into Being: Awakening to Who You Really Are

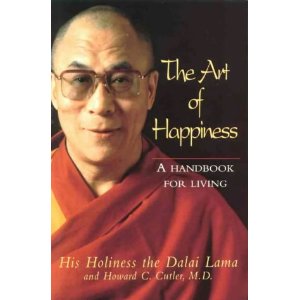

The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living, His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Howard C. Cutler, M.D.

Not many of us would disagree with His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s belief that the “purpose of our lives is to seek happiness.” But in this world of complexity, anxiety, insecurity, conflict, intolerance, anger, and hatred we might be inclined on the one hand to ignore this extraordinary book on the grounds that it is too simplistic or idealistic, or, on the other hand, to agree too readily to its premises without actually practicing the difficult inner and outer work that the Dalai Lama believes is necessary for real happiness.

The Art of Happiness is based on conversations between the Dalai Lama and Dr. Howard Cutler, a Diplomat of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Cutler does a superb job of framing the Dalai Lama’s teachings, stories, and meditations in a way that makes them come alive not just for Buddhists, but for anyone seeking real understanding.

This is a book of profound common sense. Exploring topics such as intimacy, compassion, suffering, anger, kindness, hatred, and change, the Dalai Lama makes clear that real happiness depends on transforming our deepest attitudes, the very way we look at and deal with ourselves and others. It requires “new conditioning.” For the Dalai Lama the first steps toward this new conditioning are based not on mystical or transcendental practices but rather on education, learning, determination, enthusiasm, and effort.

For the Dalai Lama, it is our negative emotions, especially our anger and hatred, that undermine our physical, psychological, and spiritual well-being and promote conflict and destruction in the world. The Dalai Lama makes clear that “’The only factor that can give you refuge or protection from the destructive effects of anger and hatred is your practice of tolerance and patience.’”

Though the practice of patience and tolerance may seem impossible with regard to the big things in our lives, the Dalai Lama suggests that we can start with the small things. “By sacrificing small things, by putting up with small problems or hardships, you will be able to forgo experiences or sufferings that can be much more enormous in the future.”

The Dalai Lama throws new light on many of our assumptions. In discussing “genuine humility” and its relationship to patience, for example, he points out that it “involves having the capacity to take a confrontational stance, having the capacity to retaliate if you wish, yet deliberately deciding not to do so.”

For the Dalai Lama, the work of patience and tolerance is a work of will that is based on inner strength, compassion, and presence of mind, not on meekness and passivity. It is this work, done with as much awareness as we can muster, that is especially needed in today’s world.

Garry Kasparov, Computers, and Time

I wrote and published this essay in 1999. A lot has changed since then, but the trend continues. For example, our phones, now themselves amazing computers, have become “smart,” smarter, very often, than those of us who use them. And the computer-driven Internet, with all the “social media” that depend on it, has begun to reshape our lives in ways we can just barely comprehend. More than ever, we are being called to take a fresh look at who we are, how these new technologies are conditioning us, and what we really need for a healthy, happy, and conscious life.

In May 1997, an IBM supercomputer by the name of “Deep Blue” beat world chess champion Garry Kasparov in a six-game match, throwing him and many others who believe in the supremacy of the human brain into a “deep” funk and a heavy analysis of what went wrong. Not long after the competition, Kasparov said that he wanted a rematch, but only if it would take place with “better conditions for a human player.” One of the conditions he demanded was more time for rest between games.

While we may question Kasparov’s overwhelming need to beat a powerful computer at chess, his reaction to his loss to Deep Blue is an important reminder for us all. Computers, unlike people, don’t need rest. They are not alive, and they operate under a completely different concept of time than we do. It is just this different concept of time that gives the computer its power to achieve so many of the spectacular results that it has achieved in science, industry, business, and almost every other aspect of society.

In spite of its spectacular results, however, and the way in which it has become an integral part of modern life, the computer has never really lived up to its early image as an “electronic savior,” an intelligent machine that would greatly increase productivity, help solve that complex problems that face both society and civilization as a whole, and give us more “free time” to do the things we really want to do. While it has freed some of us from the repetitive, menial tasks that our jobs often require, it has created an entirely new category of repetitive, menial tasks—all oriented toward keeping the computer running smoothly.

It is clear that modern life as we know it in the western world would be next to impossible without the computer. What is not so clear is the heavy price we are paying for the changes it has wrought. Like the clock, the computer has not only altered the outer world in which we live, breathe, play, and work, but it has also begun to transform the inner world of our mind, feelings, and perceptions.

The Mechanical Clock: “Time is Money”

When the mechanical clock, which may have originated as a machine to call monks to prayer, entered into the general life of 14th century European society, it had a powerful effect in ordering the daily activities of life—a situation that we take for granted today. Instead of light and darkness regulating the working day, the huge town-square clock became the taskmaster. The effect was so profound, in fact, that by the middle of the I5th century, merchants, businessmen, and others began to see that “time is money”—a radical new vision that eventually gave rise to the demand for a “portable” clock that could infiltrate and coordinate every aspect of life to increase productivity and communication.

It does not take much observation to discern the legacy we have inherited: the “portable clock” has become so much a part of our lives that it carries us with it wherever it goes. “Being on time” has become one of the core values of modern society, a value which had (and has) little meaning for traditional peoples. If we’re not on time, we’re usually late, which means that we’re supposed to be somewhere other than where we are. It is sobering to stand on any street corner in any large city in America and watch people as they rush about in order to avoid this experience. It is even more sobering to catch a glimpse of ourselves as we hurry through our day in a continual race against time.

Logic and Productivity at the Speed of Light

But the computer, with its own internal clock, is having an even more far‑reaching influence. With its ability to perform tirelessly at all hours of the day and night and to give us instant results, the computer is ineluctably conditioning us to an entirely new way of living, a way of living in which time becomes inseparable from productivity (or at least, busyness). Instead of the circular imperfection of the heavens, or even the circular perfection of the quartz timepiece, the computer gives us the linear perfection and capaciousness of “technotime.” Time is no longer, as J. B. Priestly defined it, “the horse we are riding.” It is not even money. It is rather logic and productivity at the speed of light—the relentless, “productive” march of electronic impulses through ever-smaller, more-efficient, and more-powerful microchips that process our data faster than we, as human beings, can comprehend or use the results. Time that is not timely is wasted time; a computer that is not computing or processing something is wasted productivity.

Those of us who have worked with computers know just how compelling this “processing” can be. The multi-dimensional human values of love, belief, intuition. contemplation, and perception gradually give way to the one-dimensional values of the computer: on or off, yes or no, black or white, right or wrong, logical or illogical, on time or late. And the human rhythms of work, rest, relaxation, play, and so on, all based on perceived need, are replaced by the electronic rhythms of data access, movement, and manipulation, which in a sense are not rhythms at all—at least not rhythms that can be discerned by human beings.

The computer, then, with its technotime measured in billionths of a second and its insistence on fast, efficient, logical manipulations of data, conditions us to a new image of ourselves, an image in which the speed and breadth of our own thoughts, feelings, and sensations are seen as increasingly inadequate to the challenge of living. How far this conditioning will go is difficult to foresee, but the movement from the room-sized computers of the 1970s to the “laptop” and “handheld” computers of today, like the movement from the huge town-square clocks of hundreds of years ago to the tiny watches (with their built-in alarms) of today, indicates that the process is well underway. It will become increasingly difficult to resist viewing the computer’s values of linear efficiency, speed, and logical perfection as the values by which human beings should live—and to remember that it is our imperfections and mistakes that often lead us into new avenues of creativity and growth.

If Garry Kasparov must play “Deep Blue,” let us at least be thankful that he publicly demanded better human conditions such as more rest between games. Those of us who use computers to do our jobs—to write, calculate, design, communicate, and so on—can perhaps learn something from this. Let us hope that we are sensible enough to arrange time off, too—time enough each day to get away from our computers (or whatever else consumes our time), breathe some fresh air, sense the earth beneath our feet, and quietly remember what being alive is really all about.

Copyright 1999-2010 by Dennis Lewis

Beautiful New Desert Location for “The Center for Harmonious Awakening”

We have just purchased a wonderful desert home, located not too far from Dynamite Blvd and 136th St, that will also function as The Center for Harmonious Awakening. Though our address is a Scottsdale address, we are not in Scottsdale or any other city. The house is on about 2.5 acres and has its own well for water.

The Center for Harmonious Awakening

My aim–and the aim of The Center for Harmonious Awakening–is to help us see and go beyond the boundaries of the conditioned mind–the habitual constellation of thoughts, emotions, sensations, beliefs, and judgments that each of us calls “myself”–and to help open us to the vast breadth of the life force as it manifests through us at this very moment. The work we do at the Center is to help us awaken, in a harmonious way, to who and what we really are in our essence, to the freedom of real presence and consciousness–the freedom to see and say “yes” to the miracle of what is.

Whatever noble aims we may have, paths we may be on, or necessary efforts we may make, our only real freedom is to awaken now, this very instant, to the mystery and miracle of being, to the spacious awareness that we are. It is only this immediate awakening to the deepest levels of ourselves, to the conscious source that connects us all, that will enable us to experience and manifest real harmony, intelligence, kindness, love, and compassion in our lives and bring about the transformation in the world that we all wish for.

To help accomplish this, I plan to offer frequent day-long “intensives” at the Center, including satsangs, self-inquiry, meditation, special postures and movements, and work with self-sensing and breathing.

Humming Breath Qigong

I will also be regularly teaching my recently developed qigong form called Humming Breath Qigong, which I formally unveiled to qigong teachers and students at the National Qigong Conference at the Asilomar Conference Center in June, 2009.

Here’s something I wrote about the workshop elsewhere on this blog:

“At the workshop, I presented a very simple yet powerful qigong form that I had created and practiced over many months called ‘Humming Breath Qigong.’ … Having taught and taken workshops at many NQA conferences in the past, and having experienced the fact that many teachers give their students far more than they can learn and thus end up creating unnecessary tension and frustration, I felt that this new form would be perfect for the three hours we had together. And it was. Everyone loved the form and learned the postures and movements very quickly (the inner dimensions of the form can take many weeks or months to understand and appreciate). One of the participants, who teaches qigong, has since sent me a verbal description of the movements, along with drawings, which I am in the process of editing and will eventually make available to anyone who takes the class. She also asked for my permission to teach the form and disseminate the notes to her students. All in all, this was one of the best classes I have ever taught, especially so because all the students were serious, attentive, and open to having fun as we worked together. It was also a huge help that they had all worked in one way or another with body awareness.”

And here are a few responses from people who attended the workshop (evaluations were requested from participants by the National Qigong Association):

–“Very beautiful and effective.”

–“Very knowledgeable – especially of what was happening physically and energetically.”

–“Was clearly able to share information from his extensive background with breathing.”

–“Good explanations and good use of examples and stories to illustrate the teachings.”

–“He took one practice and built on it so that we gained a depth of experience.”

–“Fabulous class!”

–“A thoughtful and methodical approach that made the material accessable and easy to learn.”

–“A lovely experience.”

–“What a surprise! Loved this qigong and will definitely take this home to practice.”

–“Very helpful in fundamental ways that will certainly enhance my life from here on out.”

I’ve also taught (and continue to teach) Humming Breath Qigong to those students who attend my Sunday and Wednesday meetings at my home in South Scottsdale.

Day-Long and Weekend Intensives

In addition to frequent day-long intensives at The Center for Harmonious Awakening, we will also offer weekend intensives. Though we will have only very limited private accommodations at the Center, there will be plenty of sleeping bag space available for weekend acitivities. There are also many motels, hotels, and resorts in North Scottsdale, only 20 minutes or so from us. On occasion, we will invite other teachers to take part in our activities at the Center.

Since we have just purchased the property, it will likely take us a couple of months to get fully organized. if you would like to be on our email list so that we can notify you of upcoming activities, please click here to fill out our email form or click on the “Contact” link (on the top of the page). Be sure to include your name and email address. Of course, we will also announce all events on this blog and on our website for The Center for Harmonious Awakening, which I am still developing. Thank you!