Announcements

Get free breathing and awareness practices, insights, and tips on my Facebook Public Figure Page

The Boundless Breath: A Gateway Into Our Unconditioned Nature

Here is a special meditation of self-inquiry, in which you will explore your breath as a gateway into yourself. Through practice of this meditation, you will have an opportunity to receive a glimpse, a taste, a sense of your inner being, your unconditioned nature.

Sit Comfortably in Silence

Begin by sitting toward the front of a firm chair, with your spine straight but supple. You can, of course, sit cross legged on a cushion if that is comfortable for you. However you sit, make sure your hips are higher than your knees.

Close your eyes, and fold your hands together in your lap or put them palm down on your knees. Rock gently forward and backward on your “sit bones” until you find a comfortable yet erect posture (if you are sitting on a chair, check your feet to be sure they are relaxed and flat on the floor). Just sit in silence for a few minutes, simply being present to yourself as you are.

Engage Your Thinking with the Question “Who am I?”

Now, with your thought, ask yourself who you are. Don’t allow yourself to be taken by any particular answer. Simply ask the question “who am I?” and observe and let go of any answers as they appear. Ponder this question with your mind for at least five minutes.

Now ask “who am I?” again, but this time, see if you can ask with your feelings. See if you can feel your whole life all at once: “Who am I?” “What’s it all about?” Allow these questions to open your heart and free you from the fixed attitudes you have about yourself and the world. Work in this way for at least five minutes.

Engage Your Sensation with the Question “Who am I?”

Now let the whole sensation of your body enter your awareness, including a sensation of your breathing. Follow your breath as it moves from the tip of your nose, through your nasal passages, into your throat and trachea, and down into your lungs. Sense how the tissues of your body seem to open like flowers as you inhale and close as you exhale. Don’t try to “do” anything. Just follow, sense, and watch. Observe in an intimate way any thoughts or feelings that take place, but don’t lose yourself in them. Continue to sense your body and follow your breathing like this for at least five more minutes. Then ask “who am I?” again, this time with your entire sensation. Let the question touch every cell of your body. Work in this way for at least five minutes.

A Gateway Into Our Unconditioned Nature

As you continue to follow your breathing, notice the pause that occurs naturally at the end of your out-breath. Include this pause in your overall awareness of yourself. The great mystical traditions have spoken of this pause, this space, between the out-breath and the in-breath as a gateway into our unconditioned nature, into our underlying reality as pure consciousness. It is in this boundless space between exhalation and inhalation, a space that is always there beneath, around, and within our thoughts, feelings and sensations, that we can more readily begin to let go of everything we believe we know about ourselves and open ourselves to the unknown.

Continue to follow your breathing, paying special attention to the space between exhalation and inhalation. Sense this space as kind of “resting place,” a place to give up your self-image, your identity, and simply come to rest in yourself. Don’t try to force anything. Just watch and sense.

As your breathing continues, and as this space begins to expand into a sense of global consciousness, let yourself become one with it. See how your thoughts, sensations, feelings, and breath are all contained within consciousness itself. Feel the miracle of yourself here and now, alive in a vast ocean of space and presence—alive in the vast ocean of the unknown.

When You’re Ready to Finish

When you’re ready to stop, let go of any experiences you may have just had and return to the whole sensation of your body and the movement of your breath from the tip of your nose down into your lungs. Then stop following your breath and just sense yourself sitting there in silence. When you’re ready, gradually open your eyes, get up, and return to your so-called ordinary life.

###

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis. You can find expanded versions of this practice in my book Free Your Breath, Free Your Life, and in my audio program Natural Breathing (where I personally guide you through the practice).

Psychological Obstacles to Authentic Breathing (From “The Tao of Natural Breathing”)

Our Inability to Exhale Fully

According to Magda Proskauer, a psychiatrist and pioneer in breath therapy, one of the main obstacles “to discovering one’s genuine breathing pattern” is the inability that many of us have to exhale fully. Whereas inhalation requires a certain amount of tension, exhalation requires letting go of this tension. Full inhalation without full exhalation is impossible. It is important, therefore, to see what stands in the way of full exhalation. For many of us, what stands in the way is often what is no longer necessary in our lives. Proskauer points out that “Our incapacity to exhale naturally seems to parallel the psychological condition in which we are often filled with old concepts and long-since-consumed ideas, which, just like the air in our lungs, are stale and no longer of any use.”* She makes it clear that in order to exhale fully we need to learn how to let go “of our burdens, of our cross which we carry on our shoulders.” By letting go of this unnecessary weight, we allow our shoulders and ribs to relax, to sink downward into their natural position instead of tensing upward. Full exhalation follows quite naturally.

Our Inability to Inhale Fully

Those of us who are unable to exhale fully in the normal circumstances of our lives are obviously unable to inhale fully as well. In full inhalation, which originates in the lower breathing space and moves gradually upward through the other spaces, one’s abdomen, lower back, and rib cage must all expand. This, as we have seen in earlier chapters, helps the diaphragm, which is attached all around the bottom of the rib cage and anchored to the spine in the lumbar area, to achieve its full range of movement downward. For this to happen, the muscles and organs involved in breathing must be in a state of dynamic harmony, free from unnecessary tension. But this expansion is not just a physical phenomenon, it is also a psychological one. It depends on both the wish and the ability to engage fully with our lives, to take in new impressions of ourselves and the world.

Freedom To Embrace the Unknown

Full exhalation and inhalation are thus most possible when we are free enough to let go of the known and embrace the unknown. In full exhalation we empty ourselves—not just of carbon dioxide, but also of old tensions, concepts, and feelings. In full inhalation, we renew ourselves—not just with new oxygen, but also with new impressions of everything in and around us. Both movements of our breath depend on the “unoccupied, empty space” that lies at the center of our being. It is the sensation of this inner space (and silence)—which we can sometimes experience in the natural pause between exhalation and inhalation— that is our path into the unknown. It is the sensation of this space that can enliven us and make us whole.

*From an article by Magda Proskauer, “The Therapeutic Value of Certain Breathing Techniques,” in Charles Garfield, ed., Rediscovery of the Body: A Psychosomatic View of Life and Death (New York: A Laurel Original, 1977), pp. 59-60.

Copyright 1997-2009 by Dennis Lewis. This passage is from my book The Tao of Natural Breathing (Rodmell Press, 2006, pp.118-119).

Dragon Thunder is a significant book on many counts. The book not only gives us a close-up, no-holds-barred view of the extraordinary life and work of Chögyam Trungpa, one of the great spiritual teachers of the 20th century, but it also shows, without equivocation, some of the many both serious and humorous complexities and paradoxes and challenges involved in Trungpa’s “crazy wisdom,” and his relentless efforts to bring Buddhism to the West.

Diana Mukpo’s intimate revelations as lover, wife, friend, and student of this remarkable human being and teacher are not only lovingly and courageously expressed, but, perhaps just as important, they are also balanced and far more objective than one might imagine.

You don’t have to be a Buddhist to appreciate the wisdom that permeates this book; you only have to be willing to see beyond the framework of your habitual self-image and your belief in “spiritual correctness,” and open to the miracle and mystery of your own being. Of course, that’s a big “only,” which will perhaps be difficult for those who would rather dwell on Trungpa’s so-called scandalous behavior (of which there are many possible examples in this book). At the very least, Trungpa’s life was unconventional, and for many, especially those who haven’t yet seen into or discovered their own dark sides, that can be threatening. As Diana Mukpo writes, “Rinpoche lived his life without the conventional reference points that most of us cling to as the anchors of our sanity.”

Though I was never a student of Trungpa’s (I was deeply involved in another teaching at the time or I might well have been), I was fortunate to hear him speak on many occasions in San Francisco and Boulder, and even asked him questions important to me at the time. No matter what his apparent state (drunk, sober, in pain, or whatever), his answers always helped open me to myself in a new and more-honest way; he was one of the most insightful human beings I have ever met. Above all, as this marvelous book so clearly shows, he never hid from or tried to bypass the messiness and uncertainty of being alive on this planet, but rather faced it with full vulnerability and awareness. And, so far as I can tell, he demanded the same from his students in the many often difficult and seemingly “crazy” conditions that he created for inner and outer work.

I remember seeing Diana (though I didn’t learn who she was until after the meeting) once in Berkeley CA (sometime in the 1970s), when she got up from her seat in the front row of the meeting room while Trungpa was speaking and walked slowly over to a nearby cold drink vending machine off to the side of the room. As I continued listening to Trungpa speak I heard the very loud sounds of the coins being deposited and the beverage container hitting the floor of the open compartment at the bottom of the machine. I watched and listened as she withdrew the drink, opened it, and returned to her seat. And I saw how quickly and easily I got lost in the judgmental thoughts that went racing through my mind: “How dare she interrupt the meeting in that way; she must be totally unconscious of what is happening here tonight; even I know that one should remain quiet while the master is speaking”; and so on. Of course, Trungpa simply kept speaking, seemingly undisturbed by her actions. I must say that I learned a huge lesson about inner freedom (and especially my lack of it) that night.

Toward the end of the book, the author gives us a direct insight into her own heart and the transformative influence that Trungpa had on her: “I know that for me, I will continue to long for him, as long as I have breath. I am left, however, not only with a broken heart but with a tremendous appreciation of life. I remember one evening sitting with him in a restaurant by the water, and he said to me, ‘You know, you should appreciate this. This is our life. This is our marriage. It won’t be like this forever.’ I laughed him off a little bit. Now, in retrospect, I realize that he was saying something profound about impermanence and the importance of appreciating one’s life. I learned from him to appreciate the world as sacred.”

The Mechanism of Mind, by Edward de Bono

The Mechanism of Mind, by Edward de Bono

“Freddie was designed as a space age pet for modern living. He is a small black sphere which is completely smooth on the outside. When Freddie is kicked he starts to roll about. To stop him you kick him again. Whenever he comes up against an obstacle he just backs away, moves along it or just changes direction as he feels inclined. The purpose of Freddie is to provide intelligent animation without the owner having to feed him, look after him or take him round the lampposts every evening.”

Freddie’s image is so intriguing that we find ourselves smiling, but not at the implication that our lives might well be similar to his own. When it comes to our mind, to our way of thinking, we resent being told that our mental processes are mechanical, and that there is no separate self or agent initiating or directing our thoughts.

Though Dr. de Bono is a physician and is currently working in the Department of Investigative Medicine at Cambridge University, England, he uses no monkeys, rabbits, rats or electronic brain probes to make his case. He seeks to convince us with models made from pins, lights, switches, blocks, jelly, water and other equally familiar materials.

Put some table jelly in a shallow dish; now spoon some hot water onto the jelly and then pour the water off: as the water melts the jelly, it creates channels. As more water is spooned onto the jelly, the patterns become more diverse and intricate. But soon, no matter where you pour it, most of the water will flow through the channels already created, thereby making these channels deeper and ensuring that any additional water will flow through them. Think of the jelly as the memory surface of the brain, and the channels as memories or associations. The flow of water through these channels is the “interpretation and recording of incoming information. . . the main point is that there is flow, and that the flow is dictated by the contours of the surface.”

In other words, the past shapes the present. But what about new ideas and perceptions? Can we receive them without their being processed by the various patterns which have accumulated through suggestion and repetition, or are we doomed to a constant repetition of past thoughts and perceptions (as the jelly model indicates)? The answer seems to demand a more precise study of the mechanics of the human mind, of the way it is “kicked” in and out of action by influences from outside as well as from within.

Dr. de Bono distinguishes between several different kinds of thought, all of which are equally mechanical, but which nevertheless differ in the results they bring. The most “primitive” form of thought is “natural thinking.” This is the passive associative flow along the contours of the memory surface. It is totally dependent on whatever happens to be accumulated at the moment. There is a momentum from cliché to cliché. “Natural thinking makes use of absolutes and extremes since these patterns become more easily established than intermediate ones.” In de Bono’s words:

“The lack of proportion in natural thinking in some ways resembles the contents of newspapers. The odd, the unusual, the emotional, all get as much emphasis as ordinary events, or more, even though the latter are much more important in real-life terms. Labels and categories are much used in natural thinking since they provide quick interpretation and firm direction of flow. There is little vagueness or indecision in natural thinking since even a slight degree of dominance in one area is sufficient to attract the flow.”

“Logical thinking” differs from natural thinking only as a result of the experience of “non-identity,” or “no.” No conveys an awareness of more than one alternative; it implies a “mismatch,” a conflict between patterns. As a result of no, one pattern or pathway is selected and another is blocked from our attention. “The effect of logical thinking is like that obtained by a farmer who directs the water to his fields by careful blocking of some irrigation channels in order to get the water to flow through the others.” The difficulty is that what may have been useful in the past may be the exact opposite of what is necessary now. Once no has blocked a particular pathway it is likely to continue doing so even when the conditions have changed. “The more emotion that was infused into the no label by upbringing, the more powerful would be its use and its effect.”

With “mathematical thinking” we come to what is supposedly the least subjective form of sequential thought. This kind of thinking, for de Bono, is based on the use of “ready-made recipes,” or “algorithms.” “An algorithm is any fixed pattern which is not derived from presented information but serves to control and sort out that information. Algorithms may be mathematical techniques but they may also be word patterns or any other type of preset pattern.” Instead of the incoming information finding its own path along the contours of the surface, specific channels are pre-cut and the information flows through them. If the “preset pattern” actually represents the given situation then mathematical thinking can avoid many of the errors of natural and logical thinking. Unfortunately, in most cases, neither the algorithm nor the choice of what it processes is itself the result of mathematical thinking.

Dr. de Bono makes it clear that none of these forms of thought can get beyond the limitations imposed by the nature of the memory surface. He therefore offers a fourth classification which he calls “lateral thinking.” This type of thinking is based on the disruption of the sequential flow of our ordinary thought:

“Lateral thinking has nothing to do with chaos for the sake of chaos. Disruption of a pattern in lateral thinking is only in order to let a better pattern form. Later the process can be repeated again. For this reason those chemical methods of disruption which work by upsetting the smooth co-ordination of the mind are useless since the smooth co-ordination of the mind is required to snap the new patterns into coherence. The art of lateral thinking is to bring about the disruption while still retaining the ability to benefit from it in terms of coherent ideas.”

How does one achieve this kind of thinking? Dr. de Bono offers a number of different methods, all of which are dependent on the ability to allow one’s thought to organize itself in a “new” way. But whether this new organization be the result of shocks coming from without, the intentional effort of turning an idea upside down, or the effort of a slight shift in attention, it is always necessary to confront what de Bono calls the “main information sin”–arrogance. “Arrogance appears in many forms. Just as one particular fixed way of looking at things leads to the arrogance of pride so another fixed way of looking at things leads to the arrogance of despair.”

How can we escape this “sin”? Dr. de Bono tells us that one way is through a “realization of the arbitrary nature and historical development. . .” of our attitudes:

“It is not suggested that the realization of the arbitrariness of patterns should lead to a loss of drive and direction. On the contrary, one realizes that patterns are useful no matter how arbitrary, and so one uses them. But uses them without arrogance, with an inquiry about better patterns, and with the willingness to change to better patterns if they should seem more useful.”

But is the interest in “better patterns” sufficient motivation to see and accept the mechanicality of one’s mind? If arrogance is not simply an information sin, if its effects are scattered through our entire being, then perhaps we do need to experience a “loss of drive and direction.” Perhaps freed for a moment from our cerebral manipulations, we will feel the need for a totally new quality of thought–one which could bring us to a wider, more fundamental sense of our existence.

This review first appeared in the journal Material for Thought, Spring 1971 (issue #3), published by Far West Editions. Far West Editions “was begun in 1968 by John Pentland, a direct pupil of G. I. Gurdjieff and president of the Gurdjieff Foundations of New York and California until his death in 1984. Its original purpose was to discover if a more impartial quality of spiritual thought can emerge when a small group of people work at writing while at the same time trying to see themselves as they are.” Though I am “the author” of this review, it was working in these special conditions that made it possible. You can click on the above link to see what issues of Material for Thought are currently available.

The Breath of Life & Meaning

Next time you find yourself in a discussion or giving a speech, take your time as you speak. If you sense that you are about to run out of breath, simply stop what you are saying and let yourself breathe for a breath or two, paying attention to the silent pause at the end of your out-breath. Rest there, recollect yourself, before continuing on. These pauses are not only good for your breathing, they are also good for your soul. They give you an opportunity to come home to yourself and see if what you are saying is worth saying and what you really wish to say.

It is important to realize that the very same same principles generally apply when you are writing articles, books, e-mail messages, discussion posts, and so on. As you think to yourself and write, you can also run out of breath and lose your connection with silence. Long concentration at your computer, typewriter, or note pad can constrict your diaphragm and result in fast upper chest breathing and insufficient oxygen to your brain and body.

Finally, does what you say and write spring from deep within, from silence? Does it help you and others reflect on what is important? Or is it simply a mechanical, associative expression of “like and dislike” or of self-love or vanity? As you learn to listen to yourself impartially as you speak and write, your words will reconnect with silence and thus carry new energy and meaning. You will discover a new breadth of both discernment and openness.

This is what I have discovered in my own life. It isn’t always easy for me to listen to what I say and how I say it (sometimes it’s nearly impossible), but such listening brings me a greater appreciation and wonder for the “unstruck sounds”* that lie at the heart of being. It is the unstruck sounds that bring real meaning and substance not just to our words but also to our lives.

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis

*From Rumi, Unseen Rain (Threshold Books, 1986, p. 12): “Listen to the unstruck sounds, and what sifts through that music.”

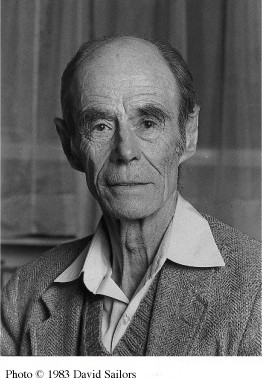

Exchanges Within: Questions from Everyday Life Selected from Gurdjieff Group Meetings with John Pentland in California 1955-1984

Those of us searching for the truth have no doubt come to see that we live our lives at a very low level of consciousness and that we lie to ourselves and others about who we are and what we understand. We have also no doubt come to see that in order to experience the truth, we must first see how deeply we resist it. We can see this resistance, for example, in the way we prefer answers to questions, or the way we constantly recoil from uncertainty and the unknown. We can also see it in the way we manipulate in accordance with our self-image the great ideas that could help motivate and guide our search—ideas related to self-knowledge, self-development, unity, freedom, pure love, levels of being and consciousness, and so on. It does not matter what teaching we follow; we are all slaves to this manipulation.

According to the great spiritual pathfinder G. I. Gurdjieff, the first step toward experiencing the truth is to see that most of the time I’m not really interested in it. It is to see that I live my life in sleep, and that to fulfill my destiny as a “three-brained being” on this earth I must wake up. The inner and outer work needed to awaken requires the help of a real teacher, as well as of a community of other serious seekers trying to work together on behalf of the truth.

One such outstanding teacher was Lord John Pentland. Until his death in 1984, Lord Pentland, who served as the president of the Gurdjieff Foundation of New York and founded the Gurdjieff Foundation of California, directed the work activities of hundreds of people throughout the United States who came to the Gurdjieff Work “in search of truth.” Exchanges Within is the record of some of the many questions that arose in relation to this search, as well as of Lord Pentland’s “answers.” The book shows his remarkable ability to translate Gurdjieff’s teachings into the exact language needed to help each seeker experience herself or himself as a living question in the face of the unknown. It is through this experience that awakening can begin.

What is the work that supports awakening? Exchanges Within probes this question on every page. Through responses such as the following one, Lord Pentland shows us that awakening requires the help not only of real ideas, but also of a deep work with attention, sensation, and energy: “The movement of consciousness is magic. Life is magic, would you agree? … You can’t understand life, it is the miraculous. … The point is, this magic is going on now and in order to experience it I have to have a very open muscle structure, an attention that contains all my energy … ”

Readers who are willing to turn toward their own deepest questions, especially the question “Who am I?”, will find valuable guidance for their search in these unparalleled, deep-reaching exchanges.

Copyright 1997 by Dennis Lewis. This brief review was originally published on my website and in the Gurdjieff International Review.

Healing Emotions: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on Mindfulness, Emotions, and Health

Healing Emotions: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on Mindfulness, Emotions, and Health, Edited by Daniel Goleman (Shambhala, Boston & London, 1997).

Healing Emotions: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on Mindfulness, Emotions, and Health, Edited by Daniel Goleman (Shambhala, Boston & London, 1997).

Reviewed by Dennis Lewis

“Can the mind heal the body? How are the brain, immune system, and emotions interconnected? What emotions are associated with enhanced well-being? How does mindfulness function in a medical context? Is there a biological foundation for ethics? How can death help us understand the nature of the mind?”

In the summer of 1991, ten well-known scientists, psychologists, meditation teachers and other scholars came together with the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala India “to grapple with these questions.” This book is a record of conversations that took place during this event—the Third Mind and Life Conference.

There are some, of course, who may say that the effort to understand reality through a dialogue between religion and science is misguided at best. But even if this were the case, Buddhism is not a religion in the ordinary sense of the term. One need not “believe in” the Buddha to practice Buddhism. For our beliefs, like our other attachments, are often what keep us from opening to reality, the miraculous emptiness that underlies the fundamental interdependence of all life.

What is unusual about Healing Emotions is the way in which it explores this “interdependence” through a continual questioning that expands our view of the world and explores relationships between things that we thought were unrelated. This should come as no surprise, however, since in the introduction we are told that “Buddhism has as principal aims the goal of transforming perception and experience and synchronizing mind and body.”

Healing Emotions explores the relationships between such subjects as cellular biology, stress, emotions, moods, headaches, immunology, visceral learning, self-esteem, virtue and morality, greed, mindfulness, death, self-acceptance, responsibility, consciousness, compassion, and much else. This thought-provoking book is a testament not only to the Dalai Lama’s far-reaching search for ways to better understand the many challenges facing us today, but also to his underlying “affection” for other human beings and their ideas and experiences.

“I believe that human affection is the basis … of human nature,” says the Dalai Lama. “Without that, you can’t get satisfaction or happiness as an individual; and without that foundation, the whole human community can’t get satisfaction either. In my day-to-day thinking, I always take into account the total environment, the whole community.”

“I believe that human affection is the basis … of human nature,” says the Dalai Lama. “Without that, you can’t get satisfaction or happiness as an individual; and without that foundation, the whole human community can’t get satisfaction either. In my day-to-day thinking, I always take into account the total environment, the whole community.”

Whether or not one believes that “affection” is the basis of human nature, it is becoming increasingly clear that the growing lack of genuine affection in modern life, of loving kindness toward oneself and others, is closely related to our lack of awareness of the “total environment.” And without this sense of the total environment—and the urgent sense of conscience that comes with it—any real transformation is next to impossible.

Healing Emotions: Conversations with the Dalai Lama on Mindfulness, Emotions, and Health