Announcements

Get free breathing and awareness practices, insights, and tips on my Facebook Public Figure Page

The Art of Travel, by Alain de Botton

I remember many years ago telling my main teacher in the Gurdjieff Work, Lord John Pentland, that I hoped to travel more in my life. He looked at me with just the hint of a smile and said simply: “Some of us find it useful to travel outside and some inside. Perhaps you should learn to travel more inside.”

My teacher was a man who traveled a great deal, both inside and out. Nonetheless, his statement aroused some big questions in me, questions that I hadn’t asked before. Other than traveling for the most obvious reasons–such as to relocate or for business or to see friends–why travel to other cities and countries at all? What was I looking for? What did I hope to experience or gain? Was I hoping to open my heart and mind to how others lived? Was I hoping to learn more about my own conditioning and limitations by traveling to other places? Would traveling inspire me? Would it make me happier, as it seemed to promise? I knew, for some people at least, that it was true, as Mark Twain said, that “travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry and narrow-mindedness.” But I also sensed some truth in what Blaise Pascal wrote in Pensées: “The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.” Perhaps both these insights can be summed up in Henry Miller’s statement that “One’s destination is never a place but rather a new way of looking at things.”

Since those early days I’ve traveled to many places (though not as many as I would like), even to Russia where I met some extraordinary people in extraordinary condtions, and the question still remains, why travel at all, especially since most of my trips were only short ones, often no more than a week or two–certainly not enough time to truly understand how people in other countries perceive and live their lives.

When I inadvertently picked up The Art of Travel by Alain de Botton, I was immediately struck not just by the book’s originality, but also by the way it resonated with some of my own experiences and questions. I had always found that the reality of travel, when I was actually present to it, had little to do with my expectations of what it would bring. And I’ve always marveled at how trips are often reduced by all of us to a few “critical moments” and “photographic highlights” that, as de Botton says, “lend to life a vividness and a coherence that it may lack in the distracting woolliness of the present.” For most of us, the destination, and perhaps a few incidents on the way, are what we most remember; the process of traveling itself is seldom remembered or discussed. We represent our travels to ourselves and others very much like the travel books we read. Here is one of the ways the author describes it:

“A travel book may tell us, for example, that the narrator journeyed through the afternoon to reach the hill town of X and after a night in its medieval monastery awoke to a misty dawn. But we never simply ‘journey through an afternoon’. We sit in a train. Lunch digests awkwardly within us. The seat cloth is grey. We look out the window at a field. We look back inside. A drum of anxieties revolves in our consciousness. We notice a luggage label affixed to a suitcase in a rack above the seats opposite. We tap a finger on the window ledge. A broken nail on an index finger catches a thread. It starts to rain. A drop wends a muddy path down the dust-coated window. We wonder where our ticket might he. We look back out at the field, It continues to rain.

At last the train starts to move. It passes an iron bridge, after which it inexplicably stops, A fly lands on the window. And still we may have reached the end only of the first minute of a comprehensive account of the events lurking within the deceptive sentence ‘he journeyed through the afternoon.'” And, of course, Botton hasn’t even mentioned here the many associations that these events arouse in our thoughts and emotions, as well as the often dull and heavy sensations they arouse in our bodies.

The Art of Travel is organized into five sections “Departure,” “Motives,” “Landscape,” “Art,” and “Return.” Each chapter begins with one of the author’s own travel experiences, then introduces paintings, photographs, poetry, and insights from famous artists, poets, novelists, and others related to that experience. Some of the “guides” on our journey are J.K. Huysmans, Charles Baudelaire, Edward Hopper, Gustave Flaubert, Alexander von Humbolt, William Wordsworth, Edmund Burke, Job, Vincent van Gogh, John Ruskin, and Xavier de Maistre.

In the book’s last chapter, “On Habit,” the author spends some time discussing Xavier de Maistre’s rather audacious book Journey around My Bedroom. De Maistre, of course, had traveled much in his life, but, according to de Botton, this book, which de Maistre believed would bring the benefits of travel to millions of people who may otherwise be too “indolent” to actually step outside their house, may leave the reader “feeling a little betrayed,” since it “becomes mired in long and wearing digressions” about his dog, sweetheart, and servant. Nonetheless, says de Botton, “de Maistre’s work sprang from a profound and suggestive insight: the notion that the pleasure we derive from a journey may be dependent more on the mind-set we travel with than on the destination we travel to.”

Alain de Botton asks: “What, then, is a travelling mind-set?”. His simple answer is “receptivity,” which requires both “humility” and the giving up of “rigid ideas about what is or is not interesting.” If one ponders this simple answer, one see that these very qualities are also required for awakening here and now to the truth of our being.

Alain de Botton ends this beautiful and insightful book with the sage observation that “There are some who have crossed deserts, floated on ice caps and cut their ways through jungles but whose souls we would search in vain for evidence of what they have witnessed. Dressed in pink-and-blue pyjamas, satisfied within the confines of his own bedroom, Xavier de Maistre was gently nudging us to try, before taking off for distant hemispheres, to notice what we have already seen.”

I recommend The Art of Travel for everyone, whether your travels take you to distant lands, unknown dimensions of yourself, or only around the bedroom you think you know so well.

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis.

Reflections on Perception & Creativity

The Endless Knot, from Wikipedia

This fact has profound implications. Everything that we see, hear, sense, smell, thing, feel, intuit, and so on manifests in some way in relation to our own psychosomatic being. Whatever the so-called “objective world” may be in and for itself, we filter, translate, and create that world based on the structure of our senses and brain. The waves, or energies, that we “perceive” and call sound and sight represent only tiny cross-sections of the vast universe of waves and energies—a universe that we can measure without understanding what it is we are actually measuring. Other, non-human creatures see, smell, sense, taste, and experience waves and energies that we cannot perceive.

THE OBJECTS OF PERCEPTION

From a scientific standpoint, we see “objects” with our eyes because our eyes, themselves objects, are structured to respond to interferences resulting from electromagnetic vibrations of light interacting with the internal forces that bind atoms together. It is the brain, itself an object, that translates these interferences from the flat images that appear on our retina to three-dimensional images including depth and distance that we call objects. And we hear “sounds” with our ears because our ears, also objects, are structured to translate certain frequencies of the wave-like motion of molecules, themselves objects, in the air into nerve impulses that our brain interprets as sounds. In short, all perception depends in one way or another on the interaction of objects.

What’s more, the pure physiological act of perception is greatly influenced by experience, conditioning, and memory. The ability to discriminate between various objects—whether through sight, sound, taste, smell, or touch—manifests itself through trial and error as the senses and brain mature, and as our memories begin to retain various experiences, comparing them to previous experiences and categorizing them based on this comparison. But, as we all know, our memories, influenced by our desires, fears, and self-image, are in large part extremely subjective, often having little to do with what was actually occurring at any particular moment.

MEMORY’S GREATEST STRENTH IS ALSO ITS GREATEST WEAKNESS

What’s more, the greatest strength of memory—its ability, to some degree, to bring the past experientially into the present—is also its greatest weakness. For it is memory that often cuts us off from truly living in the present, directly experiencing the unique miracle of each moment. We seldom see, touch, hear, think, or feel anything without our memories shaping these perceptions based on past experiences. Instead of memory being simply a functional tool at our disposal, it becomes a determining factor, shaping our perceptions and our responses to life.

This can be seen in a variety of ways. It is interesting to observe how we use memory in problem solving, for example. We often find that a particular train of thought or logic is quite effective in dealing with a certain kind of problem, and we automatically bring that solution to a problem that looks similar. But if just one element of the problem is different, which we sometimes don’t immediately see, its solution may require an entirely new approach. It is this “new approach,” that we call creativity.

Much has been written about the meaning of creativity, but one underlying tenet is the ability to look at and respond to a situation—whether it is a blank piece of paper, canvas, business problem, scientific problem, or personal problem—in an entirely new, more global way. The most creative moments are those in which memory loses its active hold on us and we are able to respond to a situation out of a total awareness of all the aspects of the situation. Memory of past experiences may be important in helping us to understand the situation, but they should not control our perception of it.

CREATIVITY & AWARENESS

Real creativity, then, is a function of consciousness. But not consciousness as thought, as verbal manipulation. If consciousness means anything at all, it means to be aware now (it is always now) of the totality of one’s situation. It means to be open to, to sense and feel, the various levels of one’s physical, emotional, and mental life, not just the parts that comprise our self-image. This awareness, which somehow unites the seer with the seen in a moment of organic wholeness, is creative. It shows us new connections and meaning, not just in words, but in sensations, images, intuitions, impressions, and actions. It frees our mind, body, and feelings from the weight and pressure of our memories, habits, and conditioning. This allows us to experience and respond to the needs and conditions of the moment from the deepest levels of our intelligence.

LOOKING IN A NEW WAY

A good way to explore the meaning of creativity in your own everyday life is to take a problem that has been bothering you and simply give up, at least for a time, trying to find a solution. Instead, let your out-breaths become long and quiet and put your energy into looking at the problem in a new way, from a new perspective, to see as many sides and levels as you can. As this occurs you’ll notice how memory enters in and begins to shape your understanding. Watch this process, take note of it, but don’t stop looking, don’t be satisfied with what memory offers up. Each time memory offers a supposed solution, simply note what it offers, give up searching for a solution, and let yourself become even more relaxed and quiet. This giving up, this relaxation of muscles, effort, and thought, will help you open to your own deepest intelligence—an intelligence that arises from more of the whole of your being.

As you explore the problem in this way, the energy that has been locked into old patterns, old knots, of thought, feeling, and muscular tension will eventually be released and will become available for pure (insofar as that is possible) perception. As Lao Tzu said: “The best knots are tied without rope.” It is pure perception, opening to openness, that untangles these knots and puts us into a truer, more creative relationship with ourselves and the world. It is pure perception that frees us, insofar as is possible, from a world created in our own narrow self-image.

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis

Busyness and Leisure: An Experiment in Spacious Presence

Everywhere we look we find ourselves and others in a rush, consumed with busyness, oblivious to the mystery and miracle of the breath of life, of being alive now and here. I am not, of course, talking about the time and effort required for “right livelihood,” the honorable work we must do for the survival and genuine satisfaction of ourselves, our families, and our communities. No, I am talking about the self-manufactured busyness that buffers us from ourselves and enables us to live without either consciousness or conscience.

Perhaps we assume that being constantly busy is not only necessary, but is also a sign to others of our importance. Or perhaps we assume that the devil does indeed find mischief for idle hands. Whatever our assumptions, however, it is often our very busyness, even the busyness of “waking up” or “creating a soul,” that keeps us turning on the wheel of unnecessary thought and action.

Who among us, for instance, can eat breakfast or lunch without trying to solve some problem or without rushing through the meal to get on with the busyness of our life? (Many of us even eat with our laptops or smart phones hard at work next to us.) Who among us is not frequently caught up in an effort to escape from boredom or discomfort or to hurry into the future chasing some dream or other? Who among us can be content with the actual demands and perceptions of now or of the unbidden leisure, a kind of inner and outer “stop,” that appears when, for whatever reason, we are able to let go of something that is unnecessary, especially the anxious thoughts that usually drive us?

To experience such leisure in our lives is to discover, both internally and externally, an empty, unoccupied space where we can unfold, live, and act without hurry. It is in this unoccupied space that we can perhaps reflect for the eternity of now on what is truly significant in our lives.

An Experiment in Breath Awareness and Spacious Presence

Next time you notice that you are about to be seduced by your need to be busy, try an experiment. Simply stop whatever you are doing (if it is possible to do so safely) and pay attention to, follow, your breathing for two or three minutes. Notice, sense, how on the in-breath your lungs are gently filled with air from the space around you, and how on the out-breath that air, no longer necessary, is gently released back into the space around you. Then notice the slight pause at the end of the out-breath. That pause is a portal into your own inner spaciousness. Sense the spaciousness that is revealed between the out-breath and the in-breath. Let yourself become one with this spaciousness as you observe the in-breath and out-breath continue to take place on their own. (To go deeper into the significance of the pause at the end of the exhalation, listen to my Natural Breathing audio program, especially The Unconditioned Breath practice at the end of the third CD (the program is also available for instant download). It is advisable, of course, to work with the entire program before trying this final practice. The Boundless Breath practice in Free Your Breath, Free Your Life will also be very helpful.)

When you have finished the formal experiment (which should also be practiced in a formal meditation setting), and when you find yourself back in the flow of action and busyness, experiment again in a spontaneous way. Pay attention every so often to the pause after the out-breath. Allow that pause–and the sense of spacious presence that it can bring–to act on you each time you are aware of it. And as the sense of spacious presence manifests more often, notice how you can be as busy as necessary, but with no hurry, no rush.

Copyright 2001-2014 by Dennis Lewis.

The Seven Secrets of Deep, Natural Breathing

Deep, natural breathing depends on the full, fluid motion of the diaphragm through its entire range of motion. The diaphragm is a dome-shaped structure that not only is the primary breathing muscle but also acts as a natural partition between the heart and lungs on the one hand, and all of the other internal organs on the other. The top of the dome of the diaphragm, located about one and one-half inches up from the bottom of the sternum, actually supports the heart. The diaphragm, which attaches not only to the ribs but also to the lower lumbar vertebrae, contracts downward as we inhale and relaxes upward as we exhale. Of course, the diaphragm moves in many other ways as well.

When our breathing is natural and deep, our lungs are able to expand more completely. This means that more oxygen is taken in and more carbon dioxide is released with each breath. When our breathing is natural and deep, the belly, lower ribcage, and lower back all expand on inhalation, thus drawing the diaphragm down deeper into the abdomen (though never below its connections to the lower ribs), and retract on exhalation, allowing the diaphragm to move fully upward toward the heart and lungs. In fact, it is the upward movement of the diaphragm on exhalation that squeezes the lungs and helps empty them of old air.

In deep, abdominal breathing, the rhythmical downward and upward movements of the diaphragm, combined with the outward and inward movements of the belly, ribcage, and lower back, also help to massage and detoxify our inner organs, promote blood flow and peristalsis, balance the nervous system, and pump the lymph more efficiently through the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system, which is an important part of the immune system, has no pump other than muscular movements, including the movements of breathing.

The first step to learning how to breathe deeply in a natural, effortless way is to sense any unnecessary tensions in your body and to learn how to release these tensions. Then, when the body needs to breathe deeply for the task at hand, it will be able to do so. Releasing unnecessary tension requires great inner attention and awareness. It requires learning the art of self-sensing and self-observation. Without sufficient awareness, without great sensitivity to what is happening inside our bodies, any efforts to change our breathing will at best have no effect whatsoever (we will quickly stop our breathing exercises), and at worst will create more tension and stress in our lives and thus undermine our health and well-being even further.

There are many effective ways to learn to sense and release your unnecessary tensions. Among the best are meditation, tai chi, qigong, yoga, bodywork, dance, Feldenkrais, and the Alexander method. What is most important in all these activities, however, is learning how to listen to your body and to how your negative, anxious, and judgmental thoughts and emotions create unnecessary tension throughout your body, thus impeding your ability to breathe fully.

Here, then, are the seven secrets of deep breathing. These principles also apply to natural, spontaneous breathing in any situation.

1. Don’t try to breathe deeply in all situations

The human organism is not designed to breathe deeply at all times and in all situations. Trying to do so will create many problems. The depth of our breath, whether it is shallow, medium, or deep, depends in large part on what it is we are doing. If we are sitting quietly reading, for example, we do not need to be breathing deeply. If we are working hard and expending a great deal of energy, however, we might well need to breathe deeply. Another situation in which deep breathing can be beneficial is when we are trying to revitalize our energy or for special breathing or healing exercises.

2. Whenever possible, breathe slowly and easily through your nose

When we breathe through our nose, the hairs that line our nostrils filter out particles of dust and dirt that can be injurious to our lungs. If too many particles accumulate on the membranes of the nose, we automatically secret mucus to trap them or sneeze to expel them. The mucous membranes of our septum, which divides the nose into two cavities, further prepare the air for our lungs by warming and humidifying it.

Another very important reason for breathing through the nose, one that many people are unaware of, has to do with maintaining the correct balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide in our blood. When we breathe through our mouth we usually inhale and exhale air quickly in large volumes. This often leads to a kind of hyperventilation or overbreathing (breathing excessively fast or breathing too much air for the conditions in which we find ourselves).

It is important to recognize that it is the amount of carbon dioxide in our blood that generally regulates our breathing. Research has shown that if we release carbon dioxide too quickly, which happens when we breathe too fast, the arteries and vessels carrying blood to our cells constrict and the oxygen in our blood is unable to reach the cells in sufficient quantity. This includes the carotid arteries which carry blood (and oxygen) to the brain. The lack of sufficient oxygen going to the cells of the brain can turn on our sympathetic nervous system, especially our “fight or flight” response, and make us tense, anxious, irritable, and depressed. There are some researchers who believe that excessive mouth breathing and the associated hyperventilation that it brings about can result in asthma, high blood pressure, heart disease, and many other medical problems.

3. Sense yourself being supported by the earth

Many of us are not very well grounded as we move through our lives. Our center of gravity is generally up in our chest and head. To breathe deeply and fully, however, requires that we begin to sense our center of gravity down in the navel area or just below. This is the area of the Hara (Japanese) or Lower Tan Tien (Chinese). It is also our natural center of gravity, which martial artists know so well.

What does it mean to ground ourselves? Is there anything that we can actually do, or is it simply a matter of being fully in the moment? Yes, there is something we can do. We can realize that in reality the earth has always supported us and that we are already grounded, and that if we don’t experience the benefits of this it is because we are lost in our thoughts, judgments, reactive emotions, and imagination.

All it takes is a bit of attention to what is actually happening right now and here–attention to the tensions that buffer us from the experience of being where we are: our tense raised shoulders, our tense feet on the ground always ready to go somewhere else, our tight, constricted breath. As we begin to observe these various habits and tendencies in ourselves, something lets go and we sense a living connection to the earth and its vast reservoir of energies. In short, we begin to relax into ourselves, which stimulates a natural, full breath.

4. Keep your shoulders down and relaxed as you breathe

Though sensing ourselves being supported by the earth will have an immediate beneficial impact on our breathing, many of us raise our shoulders in moments of anxiety, uncertainty, tension, and fear. Raising your shoulders takes the considerable weight of your shoulders off of your lungs, which stimulates upper chest breathing. Upper chest breathing is not deep breathing. It is generally shallow breathing. If you know someone with advanced emphysema, notice how their shoulders are typically frozen in a raised position. This helps them take in more air since they are not capable of taking a deep breath. So remember to allow your shoulders to drop down. Keep them relaxed.

5. Let your belly expand as you inhale and retract as you exhale

If you have a tight belly, one that does not easily and freely expand outward as you inhale, the diaphragm will have a more difficult time moving downward (and giving more space for the lungs to expand) because it is being resisted by the contracted abdominal muscles and the viscera. You must remember that everything touches something else in your abdomen, and a movement or constriction in one place influences everything around it. When you relax your belly and allow it to expand as you inhale, your viscera drop slightly down and out and thus make it easier for the diaphragm to contract downward. Then, when exhalation takes place, the diaphragm begins its upward movement of relaxation, aided by the elasticity of the diaphragm and the natural movement of the belly as it returns toward the spine.

As an experiment to see how your belly influences your breathing, intentionally suck in your belly now and try to inhale deeply (be careful not to do so too strenuously as you can hurt yourself). Then, once you are convinced that a tight belly impedes breathing, let your belly relax, put both hands on it, sense the warmth and energy coming from your hands, and allow your belly to expand as you inhale and retract as you exhale. Take several breaths in this way with your hands on your belly. Notice any differences from when you held your belly in tightly.

The fact is, with your belly held very tightly there will be much less downward movement of your diaphragm on inhalation since there is so much resistance to this movement from the abdominal muscles and viscera. And, if there is little downward movement on inhalation, there will be little upward movement on exhalation. So you will sense a lot of tension and effort in your breathing, which will often become less efficient, shallower, and faster, driven mainly by the secondary breathing muscles of the chest.

6. Learn how to free up your diaphragm

As a result of more and more mental and emotional stress in our lives, as well as the common image of the flat, hard belly that is so prevalent today, people carry a lot of unnecessary tension in their bellies, and, over time, this, combined with unnecessary tensions in the throat, chest, and back and many other factors that I discuss in my books and audio program, constricts the diaphragm and makes it difficult for it to move through its full range of motion. A lot of this tension is a result of the over stimulation of our sympathetic nervous system, which can arouse a “flight or fight or freeze” response. Over time, this diminished movement of the diaphragm becomes the norm for many people, and the diaphragm in fact weakens and loses its ability to move through its entire potential range of motion (some five to six inches in the vertical direction), which means it often becomes incapable of moving fully downward or fully upward during the in-breath and the out-breath.

When the diaphragm is unable to move freely and easily, both our inhalation and our exhalation suffer and so does our voice, and eventually our health and well-being suffer as well. (It is important to realize that it is not just the diaphragmatic movements up and down that become restricted, it is also the horizontal and other movements, as well as the shape and size of the diaphragm that are adversely affected.) If your diaphragm has weakened over the years, which is the case for many people, it will be helpful to undertake remedial action to strengthen it. The most effective way to do so is through a special program of vocalization, including humming, chanting, and singing.

7. Do not use excessive effort in deep breathing

It is important to realize that excessive effort creates tension that impedes the diaphragm and secondary breathing muscles (the intercostals) and thus undermines the breath. It is imperative, therefore, that anyone attempting to work with his or her breath use the minimum amount of physical effort necessary when doing any kind of breathing exercises and learn how to sense what happens not only in their breathing muscles but also in their entire body when they undertake these exercises. The key words here are gentleness, self-sensing, and awareness.

The reason for this is simple: the brain learns and performs best when we use the least possible effort to accomplish a given task. For thousands of years, Taoist masters have emphasized this principle through their advice to use no more than 70 percent of our capacity in carrying out physical practices related to movement and breath. The Weber-Fechner psychophysical law (the law is described in detail on page 48 of Peter Nathan’s book The Nervous System, Oxford University Press) demonstrates one reason why this is so important; it states that the “senses are organized to take notice of differences between two stimuli rather than the absolute intensity of a stimulus.” When we try hard to do something, when we use unnecessary force to accomplish our goals, our whole body generally ends up becoming tense. This tension makes it more difficult for our brain and nervous systems to discern the subtle sensory impressions necessary to help carry out our intention in the most creative way possible. And it creates tensions throughout the body that make it more difficult to breathe freely and easily and thus undermines the spontaneous flow of the breath of life. So stop trying so hard; just let yourself be breathed.

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis

To go deeper into the conditions that enable a fuller, more natural breath, and to learn how your breathing can help you open to the miracle of your being, read my latest book: Breathe Into Being: Awakening to Who You Really Are.

News of the Universe: Poems of Twofold Consciousness, chosen and introduced by Robert Bly

Sometimes I go about pitying myself,

and all the time

I am being carried on great winds across the sky.–Ojbiway

Containing 150 poems from many eras, News of the Universe, first published in 1980 and one of my most illuminating companions for more than 25 years, represents what could perhaps be called the poetry of the soul, of real feeling. The anthology brings us new, more honest feeling-perceptions of ourselves and the universe. We commune with some of the world’s great poets, including Pope, Yeats, Frost, Baudelaire, Lawrence, Stevens, Rumi, Kabir, Jeffers, Rexroth, Snyder, and many others.

Each of us will find in this volume poems that can not only help expose the rigid structure of ideas and attitudes about ourselves and the world that shape and even imprison our consciousness of the inner and outer world, a consciousness that is constantly constricted by the needs and demands of our self-image, but can also help open us to new ways of seeing, feeling, and sensing the world as it is.

Are we at all interested in seeing things as they actually are, or must we see everything in relation to our own lives? The poet reminds us:

I should be content

to look at a mountain

for what it is

and not as a comment

on my life.—David Ignatow

Inside this clay jug there are canyons and pine mountains,

and the maker of canyons and pine mountains!

All seven oceans are inside, and hundreds of millions of stars.

The acid that tests gold is there, and the one who judges jewels.

And the music from the strings that no one touches, and the

source of all water.

If you want the truth, I will tell you the truth:

Friend, listen: the God whom I love is inside.–Kabir

We are all “hungry,” says Bly, for consciousness. And so he has given us a gift of poetry that we can return to again and again for new insights into what it means to be a conscious human being, a book that can help us return to the actual feeling and sensation of the “good and beautiful,” which were so important for Socrates and Plato, and for which we are all searching, whether consciously or unconsciously.

One of the many crucial themes one finds in this volume is the realization of our ultimate death and the death of everyone we know, a realization that few of us allow into our awareness in our daily lives, but which can be tasted in moments of meditation, stillness, and silence.

There is a stillness

On the tops of the hills.

In the tree tops

You feel

Hardly a breath of air.

The small birds fall silent in the trees.

Simply wait: soon

You too will be silent.–Goethe

Bly writes: “this poem contains an experience many people have had: each time a human being’s desire-energy leaves his body, and goes out into the hills or forest, the desire-energy whispers to the ears as it leaves ‘You know, one day you will die.’ I think both men and women need this whisper; it helps the human to come down, to be on the ground. When that whisper comes, it means that the tree-consciousness, the one in the wooded hill, and the one in man, have spoken to each other. …”

The poet reminds us, however, that to come down to the ground is simultaneously to be lifted upward toward the heavens:

Earth hard to my heels bear me up like a child standing on its mother’s belly. I am a surprised guest to the air.–Ignatow

In being a “surprised guest to the air” we begin to reclaim our humanity, a growing sense of the wonder and mystery of being, and begin to live with a real question: “Who am I?”.

All the poems in this magical volume are enlivened by that fundamental question, but none for me so beautifully as this one:

I live my life in growing orbits,

which move out over the things of the world.

Perhaps I will never achieve the last,

but that will be my attempt.

I am circling around God, around the ancient tower,

and I have been circling for a thousand years.

And I still don’t know if I am a falcon,

Or a storm, or a great song.–Rainer Maria Rilke

News of the Universe is a book that I recommend to anyone who wishes not just to think in a new way about the mystery of being but also to sense and feel it directly.

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis. This review, slightly edited, was first published in the January 2009 issue of The Journal of Harmonious Awakening.

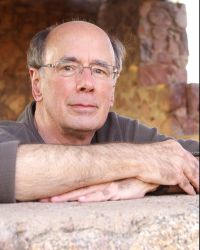

Photo of Robert Bly from Wikipedia: June 2004 at the Great Mother – New Father Conference in Maine. Photo by Fred L Stephens of Oak Ridge, TN