Announcements

Get free breathing and awareness practices, insights, and tips on my Facebook Public Figure Page

The Smiling Breath: The Quick Version

Dennis Lewis

“Smiling is science both ancient and modern. The power of a genuine smile to uplift our spirits and help heal us is profound and healing and empowering. Whether it is directed toward others or ourselves or is simply an expression of our innermost being, a genuine smile says ‘yes’ to the miracle and mystery of love and life.”–Dennis Lewis, quoted in Smile! The Secret Science of Smiling (see citation at bottom)

The next time you are feeling negative for any reason, or are experiencing pain, stress, or anxiety, think of or visualize someone who brings a smile to your face. If you are unable to do so, put a smile on your face anyway. However ludicrous it may seem to you, just “put on a smiling face.” Though it may feel unnatural at first, keep smiling for at least a two minutes and it will soon become natural—and genuine. (I’ve done it thousands of times; it works.) Once you are smiling, direct your smile inwardly into your whole body, allowing it to penetrate into all the cells, organs, tissues, and so on that your life depends on.

Now, keeping the smile on your face, rub your hands together until they are warm and put them, one on top of the other, on your navel. Sense the warmth and energy coming from your hands into your lower abdomen. Sense your breathing. Don’t attempt to control it. Notice how your belly expands or wants to expand on the in-breath and retracts or want to retract on the out-breath. As the inhalation takes place by itself, sense the air going not just through your nose but also through the smile on your face (with your mouth closed). Let the sensation, the energy, of the smile combine with the energy of your breath, and use both your intention and your attention to direct this energy down into the area that hurts or that is tense and contracted. If you are anxious, fearful, or impatient, direct the smiling breath down into your heart and the area around your navel. Be sure not to hold your breath at the end of the inhalation.

As you exhale, do so slowly and silently through pursed but relaxed lips (as though you are gently blowing on a single candle, making it flicker without actually blowing it out), and feel that any pain, discomfort, tension, anxiety, fear, or impatience is released with the exhalation. Let your next in-breath arise on its own.

As you continue this practice, sense your face frequently to be sure you are still smiling. Also, keep sensing the warmth and energy coming your hands into your navel area, letting the warmth and energy move all through your abdomen and into your spine. Each time the in-breath occurs, allow your abdomen to expand outward. On the out-breath, allow your abdomen to gently retract inward. This will help your diaphragm move through its full range of motion, which in turn will help open up all your breathing spaces.

Exhaling slowly through pursed lips ensures that the exhalation will take longer than the inhalation. This will help you relax. Don’t force your breathing in any way. The key is to keep smiling and be gentle. Practice like this for a minimum of five minutes at a time.

This is a very safe, powerful exercise that you can try any time of the day or night.

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis. You can find more complete versions of this practice, and the science behind it, in my books The Tao of Natural Breathing and Free Your Breath, Free Your Life.

You might also wish to take a look at Smile! The Secret Science of Smiling, by Elan Sun Star, a wonderful book that, in addition to numerous beautiful smiling faces, includes a section by me on The Smiling Breath (pp. 177-81), and endorsements from people like Dr. Masaru Emoto, astronaut Edgar Mitchell, Neale Donald Walsch (“Conversations with God”), and Captain James Lovell (US Apollo 13 moon landing).

The Body as the Anchor for the Senses & the Mind, from Openness Mind, by Tarthang Tulku

Here is a wonderful practice from one of my favorite books. I hope you will try it often as you can.

“It is useful to consider the body as the anchor for the senses and the mind; they are all interrelated. Feel your entire physical body. Allow your breathing to become relaxed and quiet. When your body and breath become very still, you may feel a very light sensation, almost like flying, which carries with it a fresh, alive quality. Open all your cells, even the molecules that make up your body, unfolding them like petals. Hold nothing back: open more than your heart; open your entire body, every atom of it. Then a beautiful experience can arise that has a quality you can come back to again and again, a quality that will heal and sustain you.”–Tarthang Tulku, Openness MindThe Alchemy of Consciousness

Dennis sitting with raven circling above

For these traditions, the real consciousness, the boundless presence, that is associated with our true nature is an alchemical force that can transform the human organism, opening its various perceptual centers–thought, feeling, and sensation–to new levels of sensitivity and responsiveness. This opening enables us to experience dimensions of reality unavailable to our ordinary awareness. The great traditions tell us that it is only through this higher, more-inclusive consciousness that we can uncover our true potential and destiny as human beings.

Unfortunately, most of us in the West have been educated to believe that consciousness is little more than a mental phenomenon somehow equatable to thought. We have even been taught, especially by some in the scientific community, that since consciousness cannot be studied under a laboratory microscope it must therefore be a product of our imagination. Though few of us take this “reductionism” seriously, the idea of “consciousness as thought” continues to plague society as a whole and has greatly impoverished our understanding of ourselves and others.

The Overall Structure of the Human Brain

To begin a first-hand study of consciousness, it may be helpful to review, if even in an overly simplified way, the overall structure of the human brain. Evidence shows that the human brain is composed of three basic centers or levels. These centers, each functioning as a kind of sub-brain, are interrelated networks of nerve cells, each with its own intelligence and memory storehouse. These centers, which develop at various stages in our early growth, are the inner brain, the middle brain, and the outer brain. The inner brain, or brain stem, handles the visceral, instinctive, and moving functions of the organism. It is the seat of our sensory awareness. The middle brain, or limbic cortex, mediates between our inner and outer worlds by adding emotional content and motivation to our experiences. It is the seat of our values and propels us into action. And the outer brain, or cerebral cortex, allows us to reflect our sensory and emotional experiences to ourselves and to adapt to the changing conditions of the world. It is the seat of our intellect and thought, our potential to gain perspective through a kind of “overview” of what is occurring in our lives and the ability to set aims and goals for the future.

To be fully conscious, to experience the so-called inner and outer worlds as impartially as possible, means to have full, fluid, simultaneous access to all three of these brain centers. For these centers are the instruments of experience and perception in our lives. They are the innate structures through which the raw materials of living take on specific forms and meanings. Everything we are and can become in relation to our sensations, feelings, and thoughts is somehow bound up with the proper functioning and balance of these centers. What’s more, these centers are not just located in our head brain, but are distributed and linked throughout our entire body, even in our belly and heart, as ancient traditions such as Taoism and the latest discoveries in neurobiology and other scientific disciplines have shown. It is through a global awareness of the whole of ourselves that we can get in touch with these centers and explore their interrelationships.

The Study of Attention

The study of these centers and of consciousness begins with a study of our “attention.” Our attention is the gateway into and out of these instruments of perception. Whether it is mobilized intentionally or accidentally, our attention is the thread of immediate awareness that connects our inner and outer lives. When someone says “pay attention,” for example, it is usually a reminder that we are not in touch with where we are and what we are doing at that moment–that our attention is somewhere else or has vanished altogether. Without attention, without a perceived connection to what is occurring at the moment inside or outside us, we are simply automatons set in motion with little purpose or meaning.

Experiment: Being Attentive to the Inner & Outer

To understand this better, try the following experiment. As you continue reading, allow your attention to take in not only the “outer” words on the page but also the “inner” thoughts and associations they evoke in your mind. For example, something said here may remind you of something that you read or heard recently, or you may have the thought that this is a difficult exercise, and so on. Once your attention can, to some degree, embrace both the words on the page and your associations at the same time, allow it to expand even further to include an overall sensation of your body, as well as any sounds in your immediate environment. What sensations can you experience? Are these sensations pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral? Without thinking about these sensations, simply include them in your overall experience of yourself. If you are really adventurous, try including your emotional state as well. Perhaps you find that you are still agitated about something that happened earlier in the day or that you’re feeling very good because of a compliment that someone gave you.

As you experiment in this way with your attention, take note of how easily it gets distracted. If you are very observant, you may see the exact moment when your attention is distracted from this larger perceptual context of your inner life and becomes locked on to (identified with) a particular sensation, thought, or feeling in the form of a memory, a daydream, a mental image, a complaint, a pain, an itch, a sound, and so on.

This experiment shows that, at the very least, consciousness, as manifested through the watchtower of attention, is a kind of impartial, interior illumination that cannot be equated with the functions of thought, feeling, or sensation. Indeed, the experiment shows that consciousness is what makes our experience of these human functions possible at all. We can be more or less conscious of one of these functions by itself, or we can be conscious of them all more or less simultaneously. Consciousness is thus a reality that, at least experientially, has many degrees and levels. The light of consciousness can be turned up high, as it often is in moments of great wonder, joy, or suffering, or it can be turned down low, as it is when we move though our lives mechanically, on automatic pilot.

Most of Us Live on Automatic Pilot

If we are honest with ourselves, we have to admit that we live on automatic pilot most of the time. The moment before you tried this experiment, you probably had little contact with your actual sensations and feelings. In fact, you were probably not even aware of the associative ideas and images taking place in your mind. Instead, you were no doubt lost in these associations, with little direct presence of yourself sitting and reading.

Since childhood we have been taught, mostly by example, that losing ourselves in what we experience is not only normal but also desirable. Gurdjieff called this feature of the human psyche “identification.” We glorify this state with words such as enthusiasm or passion. Since everything we do, however, ultimately involves the energies of our whole organism–mental, physical, and emotional–it is clear that conscious action, along with the immediacy of experience that grows out of it, depends on developing or discovering an awareness that is broad enough to take in as much of our inner and outer environment as possible. This awareness has nothing to do with becoming identified with, or passively losing ourselves in, something that interests us and being carried along by it. Rather it is a state of conscious engagement, a state in which we are fully present now (the only time we can be present) to whatever is taking place. This state of conscious engagement sharpens our perceptions and brings clarity to what we do. To reach this awareness, however, requires a deep thirst for understanding, for opening ourselves to who we really are.

Experiment: Catching Yourself in Action

To understand this better, observe yourself several times during the day in the middle of an activity that really interests you. It could be talking to a friend, playing tennis, working with a business associate, washing the dishes, reading a book, taking part in an Internet discussion group, holding your child–whatever you are doing. Without changing anything, simply take note of how much of yourself (and your attention) is involved in what you are doing. Don’t judge what you see. Just observe. Sometimes you’ll feel like you’ve just woken up from a kind of dream. “What? Me? Here? Now?” You’ll actually be aware of yourself, right there where you are, in that situation, functioning in a certain way. Other times, you’ll simply follow what you are doing, without much attention to your own mind or body. At still other moments, you’ll forget about the whole experiment, losing yourself completely in what is going on. See how your attention fluctuates from moment to moment. As you undertake this experiment, try not to judge anything. Just take note of what actually happens.

As you continue this experiment over the course of days and weeks you may begin to see how much of your life goes by mechanically and unconsciously, with little direct experience, and how your attention and consciousness change from moment to moment. This observation will help you look at both yourself and others from a new, more-honest perspective. You will begin to realize that many of the so-called problems of life, including not getting what you think you want, are really problems of insufficient awareness, of not being fully present either to yourself or others. Realizing this is the foundation for any genuine transformation of yourself and society.

Copyright 1995-2009 by Dennis Lewis. This is an edited version of an essay that first appeared in May/June 2009 issue of The Journal of Harmonious Awakening.

Relaxation & Letting Go: An Approach to Awakening

Dennis Lewis

For many of us, relaxation has little to do with awakening and self-realization. Instead, we mainly view relaxation, along with the various activities we undertake to achieve it, as a way to reduce fatigue and energize ourselves for what is to come, as a form of stress reduction, or simply to “unwind” and enjoy ourselves. And to be sure, these “therapeutic” views of relaxation are part and parcel of a healthy, creative, and productive life.

The great spiritual traditions, however, teach that relaxation–including the special, inner action called “letting go”–lies at the heart of inner work and awakening. The principle is a simple one, at least on the surface: unnecessary physical or nervous tension clouds our perceptive faculties. It cuts us off from the light of consciousness and from the direct inner and outer impressions of reality it can bring. Deep, conscious relaxation is what can “open” us in a harmonious way–body, mind, and feelings–to new levels and frequencies of perception. It can help us reclaim the miraculous sense of aliveness and awakeness that is our birthright.

In my own life, I have found it helpful to explore relaxation from three, interrelated levels, which I will discuss briefly here. I believe that these levels, which of course mirror our psycho-physical structure, must be understood through direct experience for relaxation to go beyond the merely therapeutic and help us to awaken from the many dreams and illusions we have about ourselves and others.

Relaxation & The Proper Use of the Body

From my experience, the first level of relaxation has to do with the proper use and alignment of the body. It is helpful in exploring relaxation to remember that almost everything we do takes place under the influence of gravity, a constant force that not only gives us weight, but frequently weighs us down. Science has shown that the majority of the impressions and stimuli that reach the nervous system do so as a result of muscular activity under the influence of gravity. And this activity includes not only our intentional muscular actions, but also various unseen antigravity mechanisms and adjustments within our body as we move through our lives.

From this perspective, relaxation has to do with finding the right posture, alignment, and balance in everything we do. Obviously, complete relaxation would be death. The heart, lungs, and other inner organs must continue their work in order for the organism to survive. And the muscular system must find the proper rhythm of work and rest, of contraction and expansion. If one set of muscles becomes weak or unbalanced, others must make up for it. And to do so they must give up their own lawful rhythms. If the abdominal muscles, for example, become too tight too often, the action of the diaphragm can be seriously impaired. And this in turn will disturb our breathing, which will have a deleterious affect on our entire being.

One of the chief manifestations of physical imbalance is unnecessary tension or strain in one or another part of our body. Unnecessary tension or strain, which keeps a muscle in a more or less chronic state of contraction, not only consumes energy but also causes the accumulation of excessive waste products in the cells, which in turn causes fatigue and reduces our kinesthetic sensitivity and ultimately our consciousness. Chronic unnecessary tension also puts our brain and nervous system into a state of constant vigilance as they attempt to bring the body/mind back into homeostasis, and this process consumes our attention and energy, leaving little of either for inner work and awareness.

Unnecessary tension and strain can have many causes–from faulty physical education to mental or emotional pressures and fears. Whatever the cause, however, our self-image, supported by our habitual thoughts, feelings, and sensations, becomes so entangled with these tensions and strains that physical relaxation alone is often not enough to eradicate them. The brain itself–and especially the sensory and motor cortexes, which play a large role in the development and maintenance of our self-image–must be reeducated through a program of conscious remedial action. And this reeducation involves all aspects of our being.

There are numerous experiments one can undertake to learn more about the conditions required for physical relaxation, but perhaps one of the most useful (for both beginners and long-time practitioners) is to lie flat on your back in what is called in yoga the “dead pose” (legs and arms on the floor). As you lie there, consciously sense any areas of tension and relaxation in the various parts of your body, including those that contact the floor. Sense your feet, your heels, your legs, your hips, your back, your arms, your face and mouth, your head. Check also under your knees, the small of your back, your neck. Notice your breathing. Is it tense and constricted or easy and open? Just be attentive to what is going on without any effort to alter it.

As you try this experiment you will see how one or another part of your body tenses or contracts itself and is unable to surrender to the support the floor offers. Don’t try to get rid of the tension or contraction. Just experience the sensation as fully as possible, allowing it to gradually release itself under the intimate influence of your attention. It may helpful to imagine that the floor is a magic carpet actually lifting your body from below. Or it may be more useful to imagine your body actually sinking into the floor. Experiment in both ways. In many cases, simple awareness of the tension in relation to the whole of the body will be enough to help the body relax more deeply. The real point of the exercise, however, is to allow the overall sensation (sensory awareness) of your body to come fully to life. When this occurs, it is much more possible to observe the way in which your thoughts and emotions are constantly influencing your physical functions, often in very constricting ways.

Relaxation & Negative Emotions

The second level of relaxation has to do with our so-called negative emotions, particularly emotions such as fear, anger, impatience, and anxiety. These emotions are related to the “sympathetic” branch of the autonomic nervous system, with its well-known “fight or flight or freeze” reflex. The main function of the “fight or fight or freeze” reflex is to ensure our survival in the face of life-threatening dangers from the outside world.

Whereas the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system, with neurons located mainly in the cranial nerves and the lower-back region of the spine, is associated with rest and relaxation, the sympathetic branch, with neurons located physically mainly in the chest and mid-back regions of the spine, prepares us for dealing with perceived dangers by taking a variety of emergency measures. These measures include increasing our heart rate and blood pressure, constricting our blood vessels, releasing sugar stored in the liver, dilating (opening up) our airways, and flooding our bodies with adrenaline and other hormones. The end result of these and other measures is to bring more blood and energy to the muscles so that we can take appropriate physical action.

To relax emotionally, we need to turn on the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system, which includes the “relaxation response.” Unfortunately, modern life is filled with constant excessive stress. And many of the dangers of the modern world are dangers we can neither fight nor flee. We are reminded of them nonstop through newspapers, television, the Internet, radio–indeed all the media of the modern world, as well as through our own revolving thoughts and conversations with friends, colleagues, and so on. So the reaction continues until the stress stops (which it seldom does) or until we grow weary with exhaustion, or until we simply stop paying attention to these threats or what is being communicated about them. In any event, this chronic “fight or flight or freeze” reaction constricts our breathing, consumes our energy, undermines our immune system and health, and diminishes our awareness of the mystery and miracle of our own being.

Interestingly, and in spite of all the problems of today’s world, a great deal of the emotional stress and fear we experience in our lives is totally unnecessary; it is self-induced, based on our imagination or on our “interpretation” of what is taking place in and around us. It is one thing, for example, to react instantaneously by jumping out of the way of a fast-moving automobile, but quite another to react instantaneously to a perceived insult. Because so many of our stressful experiences are self-induced, based on the stories we tell ourselves, we can learn to have control over them by not continuing to feed them with anticipation and negative thinking. But, of course, the first step is to clearly see the way in which we constantly contribute to our own emotional stress.

For example, the next time you feel that someone has insulted you in some way and you begin to feel hurt or angry, stop for a moment before allowing your negative thoughts and judgments to take over completely, and simply ask yourself: was the person correct in what they said to you or about you? If so, relax and be thankful that that you had an opportunity to hear the truth about yourself in that moment. Or if through your own direct awareness of yourself and your actions it is clear that the person’s insult was off base, then once again there is absolutely no need to become tense and negative. Of course, this way of looking at the truth of ourselves in action, described in various ways by G.I. Gurdjieff, requires the wish and ability to observe and think in an honest way about what we are experiencing.

Relaxation & Thinking

The third level of relaxation has to do with our thoughts, for it is our thinking that often acts as a catalyst for reactions in other parts of our being. Certain kinds of thoughts have the physiological effect of “tightening” us up, closing us to life and the movement of the life force, while others actually “loosen” us up, opening us to life and the life force. There are so many examples of this in our ordinary day that it takes only a few efforts of honest observation to verify that it is true. The effect is so profound, in fact, that in most every spiritual tradition you will find the idea that “you become what you think.”

When we begin observing and questioning our thoughts sincerely, along with the stories we tell ourselves, we see that many of them are simply not true. Our thoughts about our husbands, wives, children, colleagues, friends, enemies, and so on, for example, are often based on imagination and unseen attitudes, assumptions, and expectations in ourselves, yet they have a powerful influence on our emotions and body. We may think, for example, that we deserve more attention or respect than someone is giving us, but if we ask honestly “Is it really true that they should do so?”, we often quickly see that it’s not true at all, and that it is the thought itself that brings unnecessary suffering by arousing certain negative emotions and constrictive postures and movements.

The spiritual traditions–especially those of the East–teach us that it is our attachment to, or identification with, our thoughts and beliefs, and the assumptions and expectations that underly them, that causes most of the unnecessary tension and suffering in our lives. One need not look very far to see how this identification affects our lives. Almost all of the personal, societal, political, and global misunderstandings and violence we face are based on identification with these thoughts and beliefs.

Obviously, we cannot live without thoughts. Nor should we. We can, however, learn to “let go” of our expectations in the moment of how things should or should not be or turn out. For it is these expectations (and the fears and anxiety that often results from them) that affects our nervous system, causing unnecessary tension and often bringing about the opposite of what we desired. One finds this idea of attachment-free action in all the great spiritual traditions, and expressed with great power and clarity in the Bhagavad Gita. One acts as best one can, with one’s whole heart and attention, but without dwelling on or worrying about the outcome.

Letting go of our thoughts can itself be extremely difficult to understand, for it cannot be forced; it cannot be the result of our so-called will. It needs the support of another kind of feeling in us–an all-embracing feeling that can open us and help us become more interested in what we are actually doing and experiencing, instead of what we “should” be doing and experiencing. This feeling is sometimes described as wonder. But perhaps the beginning of wonder is innocent curiosity, the ability to take pleasure in learning more about whatever is happening in the moment. Curiosity helps us become more playful; it relaxes us and helps open us to the subtle, always-changing forms and energies of reality.

Curiosity, however, must begin with ourselves. If we stop whatever we are doing for a moment and observe ourselves as impartially as we can, we will see plenty of reason not only for curiosity, but also for wonder. “What, me, here now?” For no matter how successful or intelligent we may be and no matter how we may view ourselves or what we may believe, the truth is that we understand almost nothing about ourselves and the mystery of our existence. Accepting this lack of understanding and becoming curious about the possibility of real self-study and self-knowledge relaxes us and allows us to look at ourselves and the world in a new, more-innocent way. And with this relaxation comes not only more energy and a feeling of increased well being, but also an expanded sense of awareness. In this larger field of awareness, we find our thoughts, along with our habitual assumptions and expectations, letting go of us more and more often, thus freeing us to become more present to and welcome “what is’ without judgement. It is this presence and welcoming, this genuine “yes” response to whatever conditions that now presents us with, that lies at the heart of awakening.

Copyright 2008-09 by Dennis Lewis. This is an edited version of an essay that first appeared in The Journal of Harmonious Awakening.

For an exploration of how work with breathing and awareness can help you explore physical, emotional, and mental relaxation at a deeper level, please take a look at my books and audio program, including my most recent book Breathe Into Being: Awakening to Who You Really Are.

The Life of Milarepa, Translated by Lobsang P. Lhalungpa

Note from Dennis Lewis: I am including this book review here (a review I wrote that was first published in The San Francisco Review of Books, June 1977) in honor of Lopsang Lhalungpa, who died from internal injuries in a car accident on April 28th, 2008, at the age of 82. For those of you who have not yet read his translation of this extraordinary autobiography, I heartily recommend that you do so. This is a book that I have returned to many times over the years.

The beauty and power of the autobiography of Milarepa, the beloved Tibetan saint of the 12th century, are splendidly manifest in this new English translation, the first to appear in more than 50 years. Though finding its sources in the magic and mystery of Tibet and in the precise psycho-spiritual teachings of Buddhism, particularly the Vajrayana, The Life of Milarepa cuts across all regional and doctrinal boundaries in its celebration of the search for “indestructible truth,” establishing itself as one of the great classics of world literature.

In his luminous introduction to this new translation, Lobsang Lhalungpa, who has passed through the disciplines of the major branches of Tibetan Buddhism under many of its greatest living masters, points out that The Life of Milarepa is a “ritual drama” in which the events themselves carry “a profound knowledge of human psychology.” Every aspect of existence is included in this drama, from the most wretched to the most sublime. “We are actually witness to the creation of a spiritual world, an approach to the whole of life.”

The story opens with Milarepa’s birth, and the early death of his father. Left under the influence of a greedy and cruel aunt and uncle, Milarepa, his mother, and his sister are quickly reduced to poverty and suffering. His mother makes him vow to avenge this injustice and sends him off to learn black magic to destroy the relatives ‘down to the ninth generation.” Out of love for his mother, and through great effort and determination, Mila learns from the masters of sorcery how to cast spells and cause hailstorms, powers he uses to destroy the guests at the wedding feast of the Uncle’s eldest son and later to destroy the crops of the people of the village who are threatening his mother.

Milarepa now experiences overwhelming remorse and goes in search of a teacher who can show him the way to liberation. His meeting with Marpa the Translator, and the ordeals that Marpa puts him through to free him from delusion and from the consequences of his past acts, throw a powerful light on the process of real learning. As Lhalungpa writes: “In all of world literature there is no more dramatic portrayal of the kind of learning that a great Master provides for his pupil. No matter what else the reader may or may not take from this book, the account of ‘the ordeal of the towers’ will haunt him for the rest of his life.”

The last several chapters portray Milarepa’s initiation into the esoteric core of the teaching, his many years of meditation in order to experience in his own being the knowledge he has been given, his relationship with his disciples, and finally his miraculous disappearance into the “All-Encompassing Emptiness.” In these chapters it becomes clear that Milarepa’s transformation, though made possible by Marpa, is the outcome of his own persistent striving for compassion and for “perfect seeing.”

Simple and direct, yet evoking multiple levels of meaning, this translation of The Life of Milarepa will be welcomed by a broad spectrum of readers–from those who are interested in a gripping and poetic narrative to those who are looking for an accurate guidebook in the search for consciousness. It is one of those rare books that can penetrate to the heart, opening the reader to a sense of a deeper order in life.

Exploring Our Self-Image: Opening to the Truth of Our Lives

We all have a self-image. We all have a subjective identity fashioned over the years from the material of thought, feeling, sensation, posture, and movement. The overall image we have of ourselves, however, seldom bears any resemblance either to how others see us or to our inborn potential. As a result, most of us live stunted, illusory lives expressing only a small part of who we really are and can be.

Our self-image begins its formation during our first days on earth as a subtle interaction between our genetic inheritance and our familial, educational, social, and cultural conditioning and experiences. Depending on the kind and quality of experiences we have, this image begins to take on certain definite physical, emotional, and mental characteristics, powerfully shaping the way we see and relate to the world. Unfortunately, since a large part of this process takes place in childhood without our awareness, we tend to take our self-image for granted, as though it were given us by nature.

As we grow older, our self-image begins to crystallize and often not only cuts us off from our own inner potentials but also creates a deepening division between ourselves and others. Fortunately, however, cracks often appear in this psycho-physical structure through the shocks of our life. Difficult confrontations with our friends, families, and the everyday situations of life call our self-image–and its attendant attitudes–into question. At those moments, if we allow ourselves to experience the partiality of this image without recoiling, we may sense, at least briefly, that we are living in only a tiny part of ourselves. And, if the shock is strong enough, we may actually find ourselves in the face of the unknown: the mystery of our own being.

It is this experience of confronting the unknown, of being in question, that opens the door to awakening. If we observe ourselves honestly when we are in question, we may get a glimpse into new areas and dimensions of ourselves, as well as potentials that we never knew existed. We will also see just how powerful our self-image, our sense of “I am this” or I am that,” really is.

Most of us are unconscious slaves to our self-image. Our energies are constantly being mobilized to defend the identity that we present to ourselves and the world. This process of self-defense is an exhausting one, ultimately dulling our mind, feelings, and body, and making us less sensitive to the world in and around us.

Awakening requires that we find ways to put our self-image into question and start experiencing the truth about who and what we are. For the problem is not that we have a self-image, but that it is so partial and incomplete. At best, it expresses almost nothing of our real potential. At worst, it is fabricated almost entirely out of illusions and falsehoods.

There are many ways to become more conscious of our self-image and loosen its tyranny over us. Whatever experiments we try, however, it is important to remember that this image has been many years in the making, and that a direct assault on it will bring little benefit. However incomplete or false it may be, we depend on it for day-to-day living.

Experimenting with Our Body Image

An excellent first step in becoming more conscious of our self-image is the on-going exploration of our “body image,” of our body as we “sense” it to be. Our body image has to do with the way we experience the overall surface of our body, our skin, as well as our skeletal joints. What many of us don’t realize is that the skin is the largest organ system in the body, constituting about 16 to 18 percent of our total body weight and providing more than one-half million sensory fibers to the spinal cord. Most of us, however, have a very incomplete or faulty “kinesthetic awareness” of our bodily surface and joints. And this faulty awareness–with its many gaps, distortions, and areas of vagueness–not only impedes the overall functioning of our organism, but deprives us of many rich impressions of our physical being. When we use our body well, however, expanding our awareness to simultaneously include as many parts of ourselves as we can, our kinesthetic sense becomes more balanced and our entire organism begins functioning as a more finely tuned instrument of perception and action.

As an experiment, sit or lie down quietly for about 15 minutes after you’ve read this paragraph and simply be sensitive to your body as a whole. See if you can sense the skin everywhere on your body. If you are attentive to yourself during this effort you will undoubtedly note that there are huge gaps in your overall sensation. Check, for example, to see if you can sense your toes, behind your knees, your back, the back of your neck, your head, your nose, your eyes, your ears, and so on. If you try this experiment at various times of the day, you’ll begin to see just how weak and incomplete your kinesthetic awareness is. You’ll also begin to sense recurring bodily tensions and distortions related to various mental and emotional states, which will give you insights into your overall self-image. But even more important, as you allow impressions of what you are experiencing to enter your awareness from parts of your body that you are seldom in touch with you may feel yourself being energized in a new way, as though these impressions actually “feed” your organism at a very deep level.

As I wrote in my book Free Your Breath, Free Your Life, “Our self-image is also inevitably bound up with the particular ways we attempt to present ourselves to the world. The clothes we wear, the hair styles we choose, the furniture in our homes, the cars we drive and so on are all direct or indirect manifestations of this image, as advertising and public relations professionals know so well (it’s how they make their living). What is not so well known is that it is possible to gain access to our inner world by experimenting with these outer manifestations.”

For example, the next time you go shopping for clothes begin by ignoring the clothes you like and trying on some clothes that you don’t like. Then look at yourself closely in the mirror, being attentive to your inner reactions to what you see. Be honest about your reactions, about what you see and feel. If you’re really adventurous, purchase some clothes that you don’t like and wear them to an important social occasion (be sure to buy them from a store that will let you to return them later). You can also experiment in this way with your hair, makeup, and so on.

What these experiments show so clearly is that we are all “stuck” in a particular way of presenting ourselves not only to others, but more importantly to ourselves. We are used to seeing ourselves in a certain way, and if we alter that way even briefly our perceptual expectations are thrown into temporary disarray, thus allowing the various attitudes associated with and even underlying our self-image to become more visible. By altering our presentation it is thus possible to catch a glimpse of some of the many hidden springs of our behavior. We will also begin to see just how pervasive our self-image really is.

Experimenting with Being Right & Wrong

There is almost nothing that happens in our ordinary lives where our self-image is not called into play. When we are at work, for example, and we are criticized or praised, we all have habitual responses. If our self-image is that of a person who is usually “right” about everything, we will seldom take criticism as an opportunity to learn something new about ourselves. Instead, the criticism will make us defensive, shrinking our awareness of the moment and calling forth our suit of psycho-physical armor. If on the contrary, our image of ourselves is that of someone who is usually wrong about everything, we will again learn nothing. For again our consciousness will shrink and false attitudes of incompetence and humility will substitute for real perception.

Unfortunately, though we may agree with this analysis now, we quickly forget about it when we are in the thick of things. An excellent experiment, therefore, is to decide in advance to take one of these situations and try to respond to it in a new way. For example, if you are the type of person who is always right, allow yourself to be wrong the next time that you are criticized. And when your mind starts defending itself, don’t give in to it. Instead, simply observe your thoughts, feelings, and sensations as they arise and see if it is possible to look honestly at yourself and your motivations. If, on the contrary, your image is that of someone who is usually wrong, perhaps you should defend yourself and explain how in fact this time you are right, mustering every argument that you can imagine. Whether you’re right or wrong doesn’t matter for the purposes of this experiment. What does matter is that the repeated effort to struggle with the habitual manifestations of your self-image will help you become more conscious of it and learn more about its power over your life.

Experimenting with Winning & Losing

This kind of experimentation can be brought into many aspects of your daily life. Next time you’re playing chess, tennis, bridge, or some other sport or game with someone you habitually beat, or that you seldom beat but are about to now, allow yourself to lose without the other person knowing that you are doing it intentionally. This won’t be easy, but it will be revealing. Or if you are someone who always has to have the last word in an argument or discussion, give it up in a particular instance and watch what happens in your thoughts, feelings, and body. If, on the other hand, you’re the kind of person who seldom ventures forth with the last word, take a chance and make sure the conversation ends with what you would really like to say.

Though often difficult to actually try (in the heat of the moment we usually “forget” all about them), these experiments can be very enjoyable, since they loosen up our attitudes toward ourselves and create subtle situations in which our family, friends, colleagues, and others can relate to us in new, freer ways. Their real point, however, is not to change our self-image, but rather to help us observe it in action, to begin to include it in the larger field of our consciousness, and thus weaken its hold on us. It is important, therefore, that the experiments be undertaken in a gentle, light way and not be discussed with those around us. Otherwise we will end up having to explain and defend ourselves instead of simply experimenting. If we carry out these experiments regularly in this way they will not only help us become more conscious of what is going on in us and others, but they will also help us feel the urgency of the living question that lies at the heart of awakening: “Who am I?”.

Exploring Our Many “I’s”

What I have suggested above is really just the beginning of a possible exploration of ourselves. In our daily encounters with others we are given many opportunities to see our self-image in action, to see the precise way that it shapes these encounters. We are also given numerous opportunities to see that beneath this overall image each of us has of herself or himself, which is often referred to as “ego,” resides a plethora of personalities or sub-personalities, what G.I. Gurdjieff called “many I’s.” At one moment we can be the loving or disapproving mother or father; at another, the shrewd or inept business person; at another, the admirer or angry critic. We can be and are many things: seekers, followers, leaders, skeptics, optimists, victims, lovers, teachers, students, and so on–with all the attributes that define these different sub-personalities–though each of us generally manifests a habitual and limited repertoire of these “I’s.” Most of these “I’s,” however, are subsumed under our general self-image, which tries to control ourselves and our world and protect us from harm, and are seldom clearly seen or heard for exactly what they are. We can be “the angry critic,” for example, without really understanding the actual motivations of our anger and criticism and the defining roles they play in our lives. Yes, we mostly believe we have “good reasons” for our anger and criticism, but we seldom see how this sub-personality returns again and again, shaping our relationships with ourselves and others in often undesireable ways.

If we really wish to explore our self-image more deeply and open to the truth of our lives, we must learn how to let these “I’s,” these sub-personalities, speak to us honestly about themselves and their roles in our lives in the larger context of wholeness, a wholeness the includes all the sides of ourselves. Instead of identifying the whole of ourselves with each specific voice as it speaks (or rejecting that voice because it doesn’t fit in with our self-image), we must learn how to embrace all these “I’s” and their voices and, as they arise, welcome them into the spacious consciousness that is who we are at the deepest level. Only in this way can we discover the true freedom and joy that are our birthright.

Copyright 2008-2009 by Dennis Lewis. This is a revised and expanded version of an essay first published in the August 2008 issue of The Journal of Harmonious Awakening.

The Freedom of Simple Presence

When you check in on your breathing innocently, without any motive or effort to change it, you free yourself, at least momentarily, from your self-image, from those thoughts and reactive emotions that create so many of the problems in your life. As you check in on your breathing again and again you will begin to reside more often in the miraculous freedom of presence, the freedom underlying all the so-called problems and complexities of what you take to be yourself and your life.

Try it now while reading and pondering these words. Check in on your breathing. Simply sense what happens in your body as the breath of life moves through it. As you do so you may notice the arising of impatience and anticipation. Thoughts and emotions may arise saying you need or want to do something differently, see what will be said next, take care of some important issues, and so on. Invariably, no matter what words you use to describe them, these thoughts and emotions will generally be about changing what you are feeling right now, escaping discomfort or boredom, or doing something you believe will improve your life. You may also notice that you don’t always have to believe in your thoughts and emotions; indeed, being present to them frees you from any need to react at all.

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis. Excerpt from Breathe Into Being: Awakening to Who You Really Are (pp. 19-20)

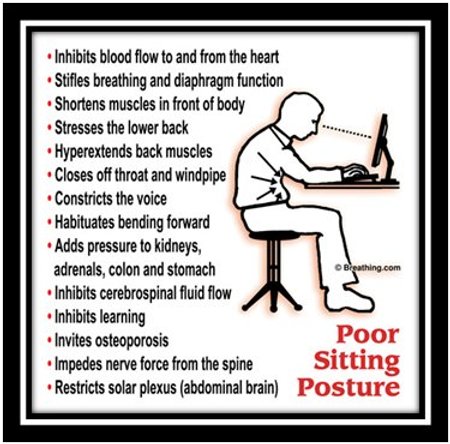

The Way You Sit Affects Your Breathing & Your Health

To sense how this posture affects your breathing, take the posture as shown and observe your breathing as you stay in this position for several breaths. What does the posture feel like? How easy is it to breathe? Take impressions from all over your body, including your belly, back, chest, and neck.

Now try an opposite, but equally poor posture: straighten up rigidly with your spine and back immobile, thrust out your chest (military style), and observe your breathing. Notice how tight and constricted your breathing is. Again, take impressions from all over your body.

Now let’s try another experiment. Sitting toward the front of your chair, rock slowly and gently back and fourth (it is also helpful to rock side to side if you wish) on your sit bones until you find a balanced and relaxed posture with your spine erect. Again observe your breathing. Notice how free and easy it is now compared with the previous two postures.

Here is a passage from Free Your Breath, Free Your Life that goes more deeply into the significance of the postures we take:

The life force expresses itself in structural configurations of many kinds. These configurations represent each organism’s way of balancing its own inherent physical form with the many inner and outer demands of living on this gravity-weighted earth. The specific positions and postures that we most often take reflect not just our needs, hopes, fears, goals, perceptions, traumas, and physical habits at any moment but also our psychophysical history and our basic stance toward living. They also reflect the degree of our openness to ourselves and others. By learning to observe our positions and postures more clearly and more often, we gain direct sensory impressions and knowledge of the forces at work in us and on us.

Every Position We Take Shapes Our Breathing

Our positions and postures, however, do more than just reflect what is happening in us. Every position and posture that we take shapes our breathing in a particular way. This fact has both negative and positive consequences. On the one hand, if we sit, stand, or lie down habitually in postures or positions that overly tighten or constrict our back, belly, diaphragm, or rib cage, these postures will over time impede the internal movements associated with healthy breathing and thus have a powerful negative influence on our breath. On the other hand, if we take a specific posture or position that helps release or open up a part of the body that is generally tight or constricted, our breathing can regain its natural coordination, elasticity, and fluidity.

Copyright 2004 by Dennis Lewis, this passage is from Free Your Breath, Free Your Life

I suggest that you experiment with your sitting posture as you work at a desk or computer, paying special attention to the influence your posture has on your breathing. If you catch yourself collapsing into the posture in the diagram above (and many of us do when we are in a hurry, anxious, tired, or stressed out), or puffing yourself up into its military opposite, stay in that posture for several more breaths and consciously sense how your breathing feels. Then get up, move around, and stretch as you continue to sense your breathing. Notice any changes in your breathing and the overall sensation of your body. After a minute or two sit down again and rock on your sit bones until to you find an erect, balanced posture as discussed above, and again sense your breathing and body. How do they feel now?

Sitting in a relaxed, erect, and balanced way has many benefits. But you will need to pay attention to your posture and breathing frequently and on a daily basis. Try it not just when you are sitting at tables and desks, but also when you sit on a couch or in a chair to read, watch TV, or talk with friends. This practice of mindfulness, of awareness, in relation to your sitting postures and their influence on your breathing will, by itself, help bring you into a more balanced alignment that will help free your breath and your life.

Copyright 2009 by Dennis Lewis. Poor Sitting Posture figure reprinted courtesy of my friend and colleague, Mike White, Optimal Breathing.